The S&P 500 has nearly doubled in the last four years. Yet many investors are left feeling more disillusioned with their investments than ever before. Some of this discontent can be combated by understanding the psychological effects of market volatility.

The S&P 500 has nearly doubled in the last four years. Yet many investors are left feeling more disillusioned with their investments than ever before. Some of this discontent can be combated by understanding the psychological effects of market volatility.

At the intersection of economics and psychology lies the exploding research on behavioral finance. This field of study often focuses on so-called heuristic biases that are observed when humans consistently make different decisions than a robot.

People strongly prefer avoiding losses to seeking potential gains. This preference is called loss aversion. Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Arnos Tversky tested this behavioral bias by asking their students and colleagues to participate in a number of probability games. One test offered a 50% chance of losing $100 and a 50% chance of winning a variable amount.

Assuming that humans are economic robots (or “econs,” according to Prof. Richard Thaler), you would expect that most would play if the winnings were just positive enough (perhaps $110) to make the time and energy of playing the game worthwhile. However, most humans are much more risk adverse than we might expect.

Kahneman and Tversky estimate that the pain people experience from a loss is nearly 2.25 times worse than the pleasure of a gain. On average, participants needed a winning purse of $225 to accept a potential loss of $100. Ouch, those losses really hurt!

To see how this would affect investors, I analyzed four years of S&P 500 data. During this same period, building from the depths of the Great Recession, a $10,000 investment would have grown to nearly $20,000.

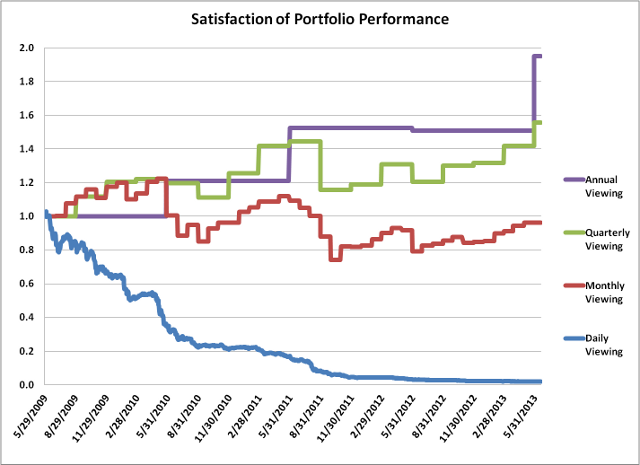

However, the perception of this growth would have been perceived quite differently by loss-adverse investors. For this test, I looked at four kinds of investors: the first group views their accounts annually, another quarterly, the third monthly, and the last group frenetically checks their account balances every day.

As you can imagine, those who check more regularly are more apt to see a negative return during that time period. During the last four years, investors who view their portfolios daily witnessed 435 negative returns, whereas those who viewed their portfolio annually only witnessed one small loss.

And when do most investors check their account balances? Do we check when the markets are on a steady march upward? No, we race to log in to our investment accounts as doom and gloom is spreading from the Middle East or Eurozone. This test does not include a preference to review finances during financial distress which would only exacerbate the disparities between perception and reality.

Assuming that each loss is felt 2.25 times as much as a gain, here is the perceived satisfaction of portfolio performance for each group of investors:

Holding the very same portfolio, those who viewed their accounts more often were much less satisfied with the performance of the market. In this test, those who viewed monthly and daily were less satisfied than when they started, which occurred during a period that this investment nearly doubled in value!

One way to balance against the tyranny of short-term market downturns is to always keep long-term performance in mind. Financial advisors typically report long-term performance numbers alongside the quarterly performance to help provide some balance to the negative perceptions of short-term market volatility. However, these anchors do not help those who have just joined a new investment manager and cannot rely on the solace of a long-term history.

Loss aversion and daily pricing of the stock markets explain one of the reasons why many people have more positive associations when thinking about their house as an investment than they do investing in the stock market. Most houses are only loosely valued once a year for property tax assessment. Meanwhile the stock market is calling out for buyers and sellers every second. You can bet that you wouldn’t feel so stable about your house value if at every moment you were being fed the value of the highest willing but erratic bidder.

I also think it is interesting to consider the effect of daily pricing and loss aversion on investment managers. I expect this group would be more powerfully affected by loss aversion than those who do not have vocational responsibilities to receive market feedback in fractions of a day, hour, or minute. Perhaps this is one reason that many wealth managers recommend portfolios that are routinely more conservative than research would recommend at each given risk tolerance profile.

Like most other human dispositions, our goal should not be to change what’s baked into the cake. Simply understanding these strong impulses can help prepare you for the emotional anxiety that market downturns are sure to provoke. As an added layer of protection, I often wonder if the most significant reason to hire an investment advisor is to have someone else to redirect the distress caused by inevitable market downturns.