While catching up on some financial blogs, I noticed that Kitces.com

covered a new process to fix 401(k) rollover mistakes.

While catching up on some financial blogs, I noticed that Kitces.com

covered a new process to fix 401(k) rollover mistakes.

The IRS has a rule that if you are doing a rollover for an IRA (or IRA-like account, such as a 401(k)), you have 60 days to complete that process. Sixty days might sound like a fairly long time, and usually it is plenty of time to have the first company send you a check and then deposit that check into a new (or existing) account. Even if the first holding company drags their feet for a few weeks and you have to open a new account (which might take a few days to a week) and then you deposit the check and it takes a few days to clear, 60 days is usually enough time to make all that happen.

But what if you experience a tragedy in the midst of that process? If your home has been destroyed in a natural disaster, are you going to remember the 60 day time limit on your rollover?

For this and 10 other worst-case-scenarios, the IRS will now cut you a break, as long as you rectify the error and complete the rollover as soon as possible upon realizing you haven’t finished the process. This “as soon as possible” guideline means within 30 days if you can (this is the “safe harbor” time period), expanding your window to 90 days total. This grace period is a hardship extension, and only applies in certain circumstances.

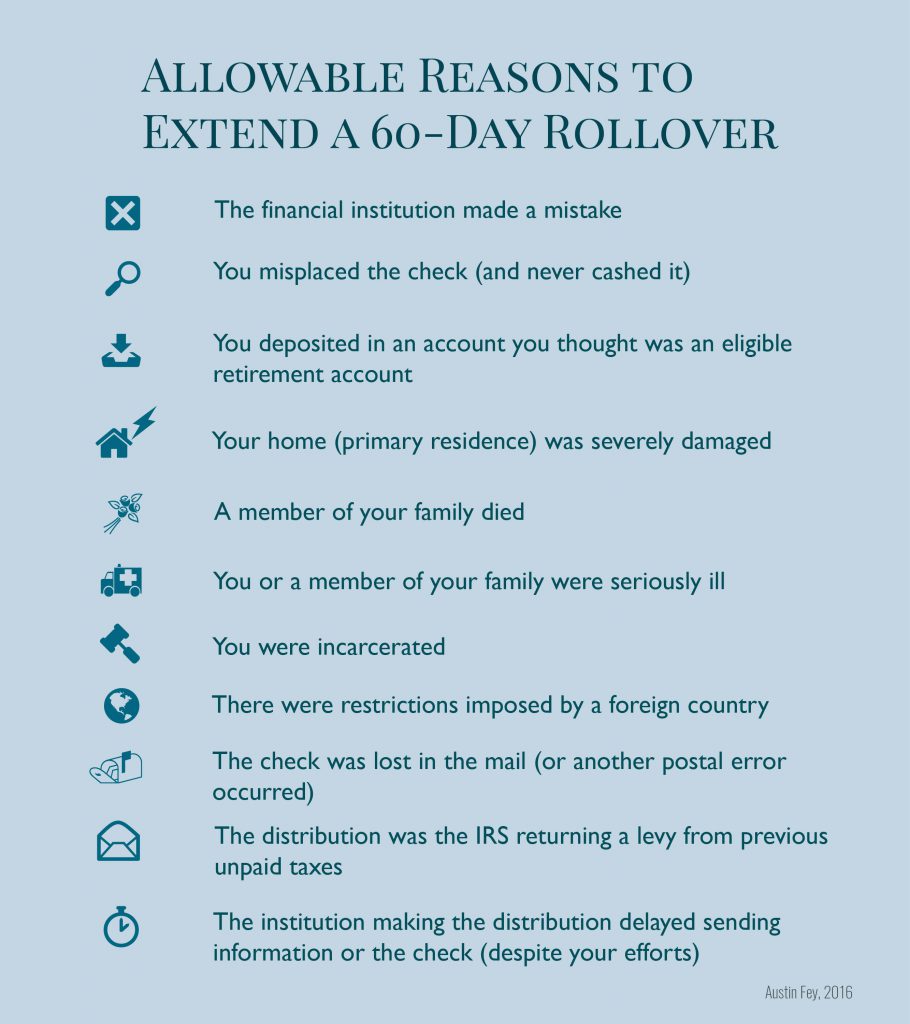

Here are the 11 reasons the IRS will allow you to exceed the 60-day rollover period and not fine you for the mistake:

- an error was committed by the financial institution receiving the contribution or making the distribution to which the contribution relates;

- the distribution, having been made in the form of a check, was misplaced and never cashed;

- the distribution was deposited into and remained in an account that the taxpayer mistakenly thought was an eligible retirement plan;

- the taxpayer’s principal residence was severely damaged;

- a member of the taxpayer’s family died;

- the taxpayer or a member of the taxpayer’s family was seriously ill;

- the taxpayer was incarcerated;

- restrictions were imposed by a foreign country;

- a postal error occurred;

- the distribution was made on account of a levy under § 6331 and the proceeds of the levy have been returned to the taxpayer; or

- the party making the distribution to which the rollover relates delayed providing information that the receiving plan or IRA required to complete the rollover despite the taxpayer’s reasonable efforts to obtain the information.

Here is the procedure to rectify the situation:

Write a letter to the financial institution receiving the rollover giving the details of the rollover (including the amount of money rolled over) and the reason or reasons for the late payment.

The IRS has provided a sample letter in their publication on the new ruling.

You should also keep a copy of the letter with your tax documents should the IRS audit you or ask questions about the late rollover. Keep any other documentation you have on the whole process as well.

This does not change the rule that you are only allowed one IRA rollover per calendar year. An IRA Rollover is not the same thing as a trustee-to-trustee transfer, which is where you move money from one custodian straight over to another custodian without ever handling the money yourself. If the money never comes to you directly in a check or bank account deposit, you can safely do as many of those transfers as you like. Some institutions also refer to these as rollovers, which is confusing, but the key is know where the money is going.

Ask questions before moving money out of IRAs and 401(k)s to make sure you comply with IRS regulations. It is worth putting off a move for a few weeks or months to make sure you’re complying rather than paying a stiff penalty for an additional rollover (not to mention receiving a bundle of extra taxable income which could push you into a higher tax bracket).

While “the dog ate my 401(k) rollover” is not an acceptable excuse where the IRS is concerned, it is good to know that in the event of a tragedy, you have a little extra time to collect yourself instead of paying thousands of dollars in fines.

Photo by Scott Graham on Unsplash