There will always be swindlers masquerading as investment advisors. You can learn to recognize such people by their over-the-top lifestyle. Avoid them at all costs.

There will always be swindlers masquerading as investment advisors. You can learn to recognize such people by their over-the-top lifestyle. Avoid them at all costs.

The differences between the manager of a Ponzi scheme and a model citizen are almost imperceptible, which is not surprising. Those who would perpetrate a Ponzi scheme are usually not the demons everyone makes them out to be. And they are obsessed with appearing successful.

This fixation on appearances, however, is the red flag. If you are the millionaire next door, you know that frugality is one of the marks of an effective financial advisor.

But you may have to train your eye to recognize an immoderate lifestyle. If someone in business is worth $300 an hour, some apparent extravagances may in reality be productivity gains.

For example, if you hire a chauffeur to drive you to and from work each day so you can be productive, society gains. If you hire a gardener so you can continue contributing in your area of expertise, society gains. And if you hire a butler or a chef, so long as you employ someone else for less than $300 an hour, society gains.

Productivity gains are not synonymous with a lavish lifestyle, and with some careful observation you can learn to discern the difference. Productivity gains are all about function, and if you discover them you will find out accidentally. In contrast, the whole purpose of an extravagant lifestyle is to be noticed.

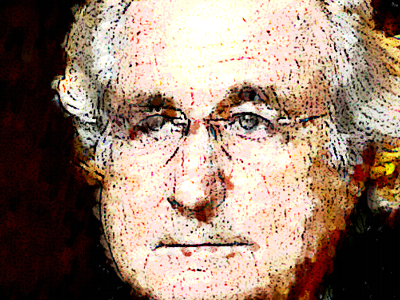

Consider Bernie Madoff. He and his wife lived in a $7M penthouse apartment in New York City and a house worth $3 million in the Hamptons. They also owned a $9.3 million Palm Beach mansion. Plus they maintained a $1M million chalet and two boats on the French Riviera.

They spent an average of $100,000 monthly on the corporate credit card on chartered jets, limousines, top hotels, fine wines, world travel and shopping. When they drove themselves, they rode in style in a BMW and or one of two Mercedes. Madoff bought a vintage Aston-Martin for his brother as a company car. The couple owned a Steinway concert grand piano worth $39,000. Madoff purchased tickets at the Mets Citi Field at $40,000 a season.

Madoff was also a prominent philanthropist, but his interests were anything but altruistic. He started the Madoff Family Foundation and gave to charities, which in turn invited him to serve on their boards. Madoff then invited them to invest their endowments.

He and his wife also gave more than $200,000 to the Democratic Party. He gained high-level connections to those in Congress who write the laws and are supposed to provide regulatory oversight. Madoff was one of the first to exploit kickbacks for brokerage order flows. He argued they should remain legal and not alter the price that customers received. His connections prevailed.

The Madoffs themselves owned $62 million in securities and $45 million in municipal bonds. They loaned their sons $22 million and $9 million, respectively. Oddly enough, having siphoned billions, the couple only has a net worth of about $823 million.

Wealth is what you save, not what you spend. That’s why an ostentatious and excessive lifestyle is a red flag for an investment advisor. The middle class buys liabilities like boats and cars. The rich buy investments. If Bernie Madoff had bought businesses and investments, he would be able to make restitution of those initial investments. He might even be able to pay a fraction of the gains he claimed to have.

We all wonder what happened to the $65 billion. Much of it was phantom gains, and a lot of it was simply spent a million here and a million there. Excessive spending is a warning sign that your advisor doesn’t understand wealth building personally.

In April this year, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charged Shawn Merriman of Aurora, Colorado, of collecting $20 million in a Ponzi scheme “to support his lavish lifestyle.” He lied to investors, reporting “impressive and consistent annual returns” as high as 20%.

Merriman was known for showcasing his high-end art collection. U.S. marshals seized hundreds of works of art including some by Rembrandt and Picasso from his sprawling three-story home. Also seized were a silver Aston Martin, 1932 and 1936 Auburns and a 1932 Ford Highboy.

This spring the SEC also filed charges against Pennsylvania advisor Tony Young for allegedly stealing $23 million from investors to “support a lavish lifestyle for his family, including payments for expenses related to horse ownership and racing, construction, boats, limousines, chartered aircraft and other luxuries.” That lifestyle included an opulent vacation home in Palm Beach, Florida, near the Madoffs’ vacation home. Young also lied to accountants who prepared statements and claimed his losses in 2008 were only 5.8%.

Ponzi schemes are often discovered after market downturns when investors make the mistake of fleeing to safety. They want to take their stellar returns and put the money someplace safe while the storm blows over, only to find that no money is really there.

Additionally, the news cycle runs in themes. After the Madoff scandal, every Ponzi scheme became national news. The theme, played over and over, is that all financial services, from Fannie Mae to AIG, are rife with corruption and mismanagement and need more government regulation.

But more control won’t protect you from dishonesty. More law can’t protect you from an unethical person. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had direct congressional oversight. Madoff was good friends with the regulators. Regulation is more likely to be used politically than responsibly.

Your best defense is to engage an advisor whose daily practices reflect ways to safeguard the money under his or her fiduciary care. As part of identifying such an advisor, make sure there is a mutual understanding that an ostentatious lifestyle is not a valid financial goal.

See also:

- Safeguard #1: Do Not Allow Your Advisor to Have Custody of Your Investments

- Safeguard #2: Walk Away from “Too Good to Be True”

- Safeguard #3: Insist on Publicly Priced and Traded Investments

- Safeguard #4: Buy Investments That Trend Upward

- Safeguard #5: Understand Your Investment Strategy

- Safeguard #6: Recognize And Avoid Financial Hooks

- Safeguard #7: Avoid Investment Advisors Who Sugarcoat Reality