The economics of health care are the awkward combination of cost and caring.

We’ve been helping Michael Kirsch, a practicing physician and newspaper columnist, to answer some of his patients’ most vexing questions. Question 7 is “Why do physicians permit, if not encourage, futile medical care?”

Who is to say what medical care is futile? Much of the costs of health care simply try to manage the dying process. At the end of life there are rarely any good answers. We are all mortal. Every effort to save the patient from dying ultimately proves futile. The only debate is how many years of life can be gained from a treatment versus the outcome if no course of treatment is pursued.

Medical care is measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). QALY measures how many years of additional life can be gained by any medical procedure. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has set the cost threshold of one year’s worth of quality life at $50,000.

In previous articles we discussed that some screening tests don’t save money even if they save lives. As a result, we’ve been accused of putting costs over caring. Nothing could be further from the truth.

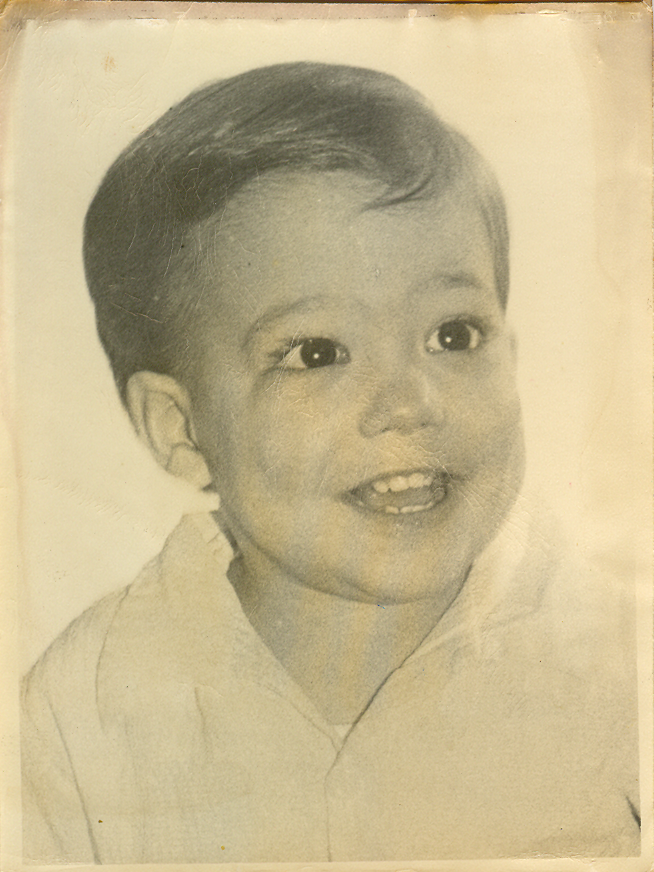

David’s brother Mark was born in March 1955. From February through May the government set off 14 different open air nuclear detonations in Nevada. The radioactive fallout drifted over the eastern United States. In September Mark was diagnosed with acute leukemia.

Mark’s parents took him to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, because they were doing research on leukemia. He was given six months to live.

Mark was part of the first wave of alarming increases in cancer as a result of nuclear testing at a rate of more than three per month. For his parents, no amount of money was too much if it offered even a slim chance of success.

In a free market equilibrium, everyone is satisfied with the outcome. There are no shortages, no surpluses. The suppliers are happy with the quantity sold and the price set. The consumers are happy with their decision in response to the price. Some consumers are excited to have made a good deal. Others are grateful they avoided overpricing.

Because individuals can weigh the cost and the benefit for themselves and make their own decisions, they can choose what will satisfy them.

No amount of centralized planning will allocate resources better than supply and demand. One reason that physicians provide futile medical care is because patients demand it.

Mark had a brief remission and came home for Christmas. He appeared healthy and happy. But then symptoms returned. He died when he was 18 months old. Was the care futile?

In 1955 the survival rate was effectively zero. Today, as a result of research, children with leukemia have a 5-year survival rate of 85%.

Who is to say what constitutes futile medical care?

In 2008 David’s father had a life-threatening abdominal aortic aneurysm. The first surgery was ineffective and had to be redone. After surgery he was unconscious for two weeks with ventilator-associated pneumonia.

As an 82-year-old, it wasn’t clear that he would make it. But this past summer he celebrated his fifth wedding anniversary. This fall he is traveling to Italy.

My grandmother used health care services extensively. It wasn’t clear the expense would pass the $50,000 a year threshold of the CDC. We thought we might lose her several times, and yet she lived to be almost 100.

Physicians should provide their services to everyone who is willing to pay either out of pocket or for insurance to cover their needs. They should not be burdened with trying to decide who is the most deserving or what care is worth delivering.

But these death-panel discussions only come into play when governments try to override free markets with centralized planning.

Third-party payer systems drive up demand so physicians have an incentive to encourage care no matter how futile. Thus if the government is willing to pay for a scooter, companies will advertise the Medicare coverage and help claimants fill out the necessary paperwork to qualify.

Physicians have an incentive to encourage the use of their services as well. And patients covered by a third-party payer system have little incentive to refuse them.

Centralized planners are no more qualified to distribute health care than they are to distribute organically grown vegetables. The market is both fairer and more efficient at allocating such resources.

The market also leaves individuals free to make the difficult decisions regarding what levels of insurance or health care are worth the expense and which are not.

Striving to live is admirable. Fighting to save a life is also a virtue. Accepting our mortality can also be a virtue. There are no good answers at the end of life. We should not judge the difficult choices of others even if the struggle seems a waste of resources to us.

Only under a socialist or collectivist model when we are required to pay for the choices of others do we begin to begrudge letting others make their own choices.

Often there are no easy decisions toward the end of life. Our advice is to remember this and not blame yourself because it did not turn out well.

One helpful document is an advanced medical directive. The organization Aging with Dignity provides a free and relatively easy way to think through these issues. Their document “Five Wishes” lets your family and doctors know:

- The person you want to make health care decisions for you when you can’t make them.

- The kind of medical treatment you want or don’t want.

- How comfortable you want to be.

- How you want people to treat you.

- What you want your loved ones to know.

These aren’t easy questions. But the Five Wishes document has a simple PDF format that lets you cross out whatever you don’t want. And one legitimate option in each case is “I want to have life-support treatment.”

We can only afford to allow others the freedom to strive against death when we are not trying collectively to subsidize it.

This blog post is part of “The Economics Of Healthcare series“.