A balanced portfolio is comprised of “non-correlated investments”, which means the investments don’t move in sync with one another. This is precisely what makes the portfolio balanced – when one investment crashes, they don’t all crash.

One of the most common reasons investments move lies with inflation and the devaluation of the dollar. The extent of the movement is different for each asset class.

Inflation and the devaluation of the dollar are dangers for the US bond-portion of a portfolio. With all fixed income you get back a fixed number of dollars, but inflation and dollar-devaluation threaten the purchasing power of those dollars.

Normally, half of the six asset classes provide direct protection against a falling dollar: Foreign Bonds, Foreign Stocks, and Resource Stocks. Obviously these three categories do better if the dollar decreases in purchasing power, but they do worse when the dollar increases in purchasing power. We believe that having a portion of your portfolio hedged against a drop in the dollar’s purchasing power is better than putting all your eggs in the basket of any country’s currency value, even the United States’.

Of all the investing risks we face, inflation is the most commonly overlooked and most certainly experienced. You might think with all of the Federal Reserve’s Quantitative Easing that a devaluation of the US dollar is inevitable, but the effect of the money supply in the economy is tempered by that money’s velocity, which is at a 50 year low. An increase in money supply (M2) compared to GDP would cause the dollar to lose value, but if the new money being pumped out by the Federal Reserve doesn’t circulate quickly, that effect will be delayed. Until the velocity of money picks up, the dollar’s decrease in value is not inevitable. This delayed effect can be seen in Japan’s attempt to lower interest rates to stimulate their economy.

Foreign bonds represent 35% of the world’s investable assets making them one of the largest asset classes, but turning to foreign bond indexes to hedge against the devaluation of the dollar is not necessarily the best idea.

Foreign bond indexes are generally cap-weighted. That means that the amount of the index invested in a country is proportional to that country’s debt relative to total global debt. The result is that when Greece increases its debt, foreign bond indexes increase their allocation to Greek bonds, and everyone trying to follow the index buys more Greek debt. We don’t think that is a great bond strategy.

When you look at sovereign debt and deficit by country, there are a number of countries whose handling of their money supply, deficit, and debt are bad enough that we call them the ring of fire. Greek default is not guaranteed, but we think it is important to have foreign bonds which are weighted away from these more dangerous countries.

One way to do that is to invest in emerging market bonds. Emerging market bonds are not without risks. But developed-market countries are averaging a 100% debt-to-GDP ratio while the same ratio for emerging markets has been dropping as their economic activity grows. Currently, debt is only about 40% of what they produce.

Another way to invest in foreign bonds while avoiding countries which are high in debt and deficit is to pick bond funds which are limited to a single country. There are a few we hope are going to hold their value better than the Euro and the Yen. One of those is the WisdomTree Australia & New Zealand Debt ETF (AUNZ):

WisdomTree Australia & New Zealand Debt Fund (AUNZ) seeks a high level of total returns consisting of both income and capital appreciation. The Fund attempts to achieve its investment objective through investment in debt securities denominated in Australian or New Zealand Dollars.

Most of AUNZ is in Australian dollars, with about 12% in New Zealand dollars.

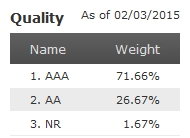

The bonds comprising AUNZ are high quality:

At first glance, AUNZ did not have great returns in 2014: -0.47%. But even that poor return was better than the -2.43% you would have experienced investing in the foreign bond index over 2014.

Most of the under-performance was due to exchange rates between the Australian dollar (AUD) and the US dollar (USD).

At the start of 2014 the exchange rate was: 1 AUD = 0.8927 USD

And at the end of 2014 the exchange rate was:1 AUD = 0.8171 USD

That means that the US dollar gained against the Australian Dollar by 9.25% [ as computed by (0.8927 / 0.8171) – 1 = 0.0925 ] and the Australian Dollar lost 8.47% against the US Dollar [ as computed by (0.8171 – 0.8927) / 0.8927 = -0.0847 ]. (To understand why these two numbers (9.25% and -8.47%) are different, consider that if the US dollar gained 100% against another currency, the other currency would only have lost 50% of its value against the dollar.)

One way to look at AUNZ’s performance is that it had a performance of -0.47 after the Australian dollar dropped 8.47%.

That means that aside from the currency exchange, AUNZ actually gained 8.00%.

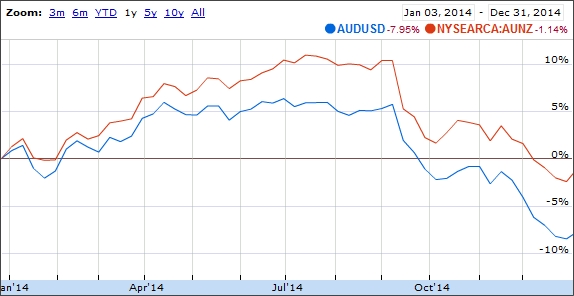

Here is a chart of the price of the Australian dollar (AUDUSD) against AUNZ:

This chart only shows the price difference 6.81% (-1.14 – -7.95) which when added to some interest (1.19) probably produced the 8% return in Australian dollars. Translated into US dollars, the 8% return lost 8.47% in the exchange over the year to produce a -0.47% return in US dollars.

Currency exchanges can go both ways, but in this case the currency exchange caused AUNZ to perform poorly compared to how it might have otherwise performed without the exchange rates changing.

The US dollar may have gained 9.25% against the Australian dollar, but that the Euro and Yen fared worse: the US dollar gained 13.9% against both. [ (0.826 / 0.7255) – 1 = 0.13.9 Euro; (119.839 / 105.2417) – 1 = 0.139 Yen]

Even in a year that the US dollar strengthened against many foreign currencies, the countries with the most economic freedom appear to have held the value of their currency better than the Euro and the Yen with an average loss against the dollar of only about -6.12%. The Swiss Franc was the worst at -10.29% over 2014.

Investors often translate an 8.47% change in relative currency values as, “The US dollar is strengthening against the Australian dollar.” This is a mistake.

As you can see from the chart above, the Australian dollar was up over 5% mid-way through the year before dropping in the second half of the year as the US dollar strengthened. Not only is “past performance no guarantee of future results,” but the two are not even loosely correlated.

Foreign bonds from countries that are less likely to devalue their currency (by inflating their currency or issuing bonds) can help diversify your bond portfolio. The returns of AUNZ over 2014 provide an illustration of how that can help even in a year when foreign bonds did not perform well.

Both the authors and the clients we manage often invest in the investments mentioned in these articles.

Photo used here under Flickr Creative Commons.