Rebalancing from stocks into bonds reduces your returns on average since bonds have a lower average return. But there are decades of very choppy markets where even rebalancing an allocation of stocks and bonds can boost returns.

We group our top level asset categories into bonds and stocks. We call the bond group “stability” and we call the stock group “appreciation.”

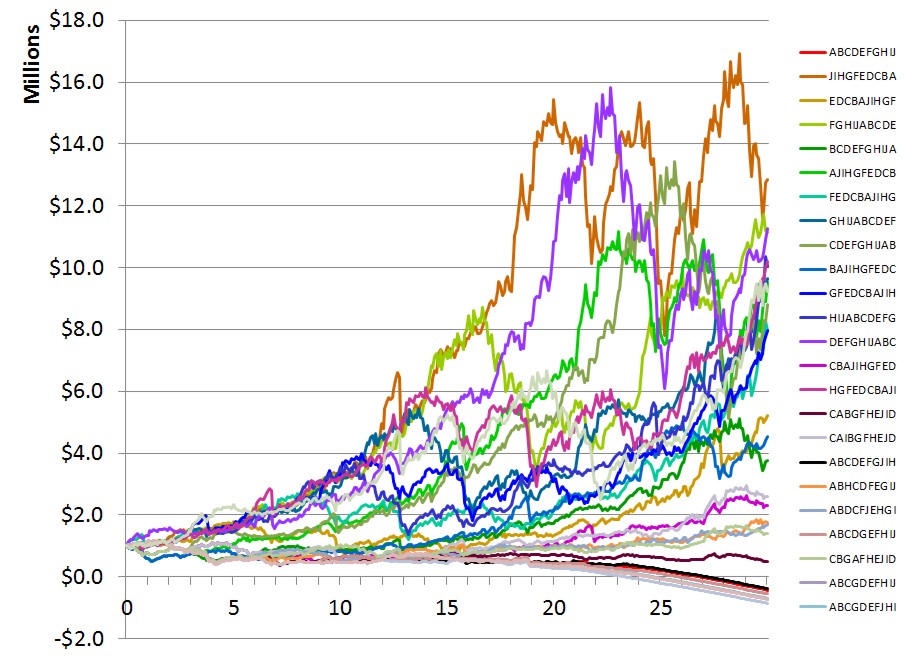

I did a study which simulated a typical 30-year retirement portfolio of $1 million. For returns I used 10 sets of three year’s worth of returns beginning in each of the following years: 1975, 1978, 1984, 1987, 1993, 1999, 2002, 2005, 2008, and 2011. I purposefully left out the three year periods beginning in 1981, 1990 and 1996 simply because their stellar returns often in both bonds and stocks made finding allocations which failed much more unlikely.

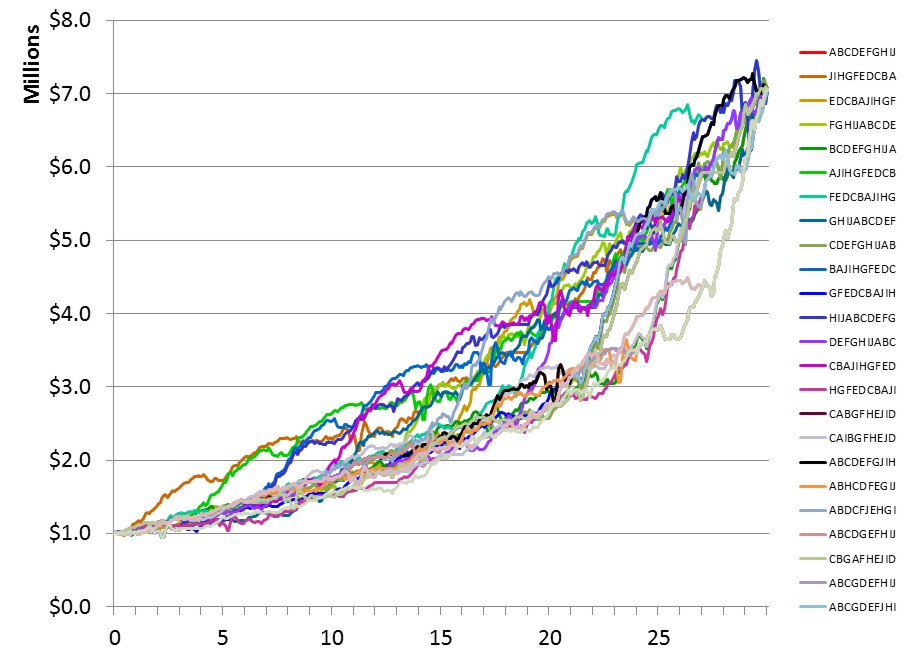

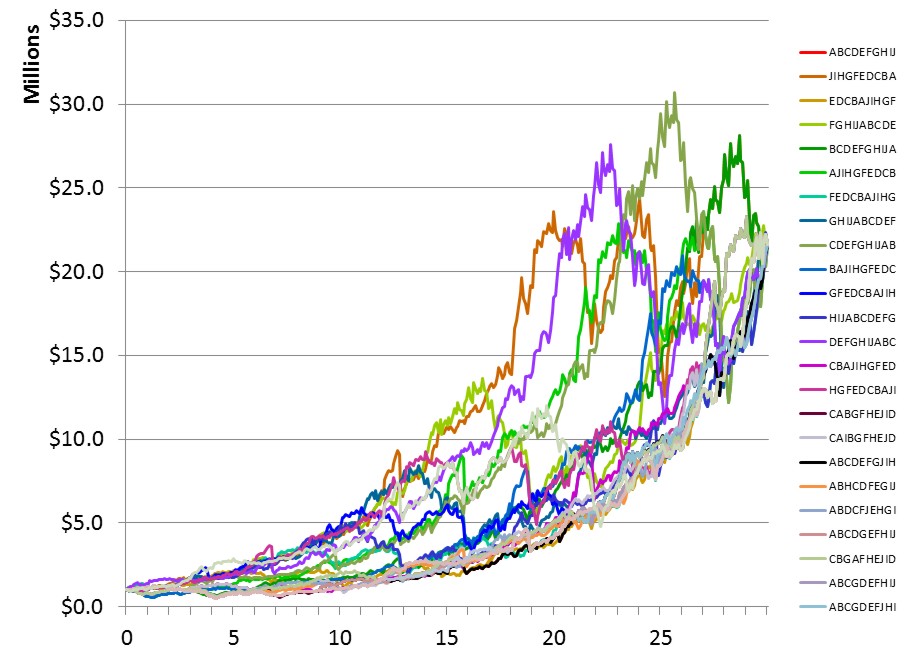

In one analysis, I used them in order. In another analysis, I used them in a different order. The total number of permutations is over 3 million. I ran a small sample of just 30 of these potential return sequences using the historical returns of the Barclay’s Aggregate Bond Index and the S&P 500 Total Return Index.

In all 30 scenarios, an all-bond portfolio grew from $1 million to $7.0 million and an all-stock portfolio grew from $1 million to $21.6 million.

|

|

The path to reach the $21.6 or $7.0 million was different depending on the sequence of returns. But, without any contributions or withdrawals, each portfolio’s scenarios ended up in the same place after 30 years.

This leads many investors to believe that so long as they are willing to endure the ride, it is better to invest entirely in stocks. They believe that this will ensure the maximum amount of money.

Such thinking is of the source of risk tolerance questionnaires. Financial advisors often ask their clients a series of questions to determine how much risk they can tolerate. The idea is to push clients to take the maximum amount of risk they can tolerate to achieve the maximum amount of return.

This approach is wrong.

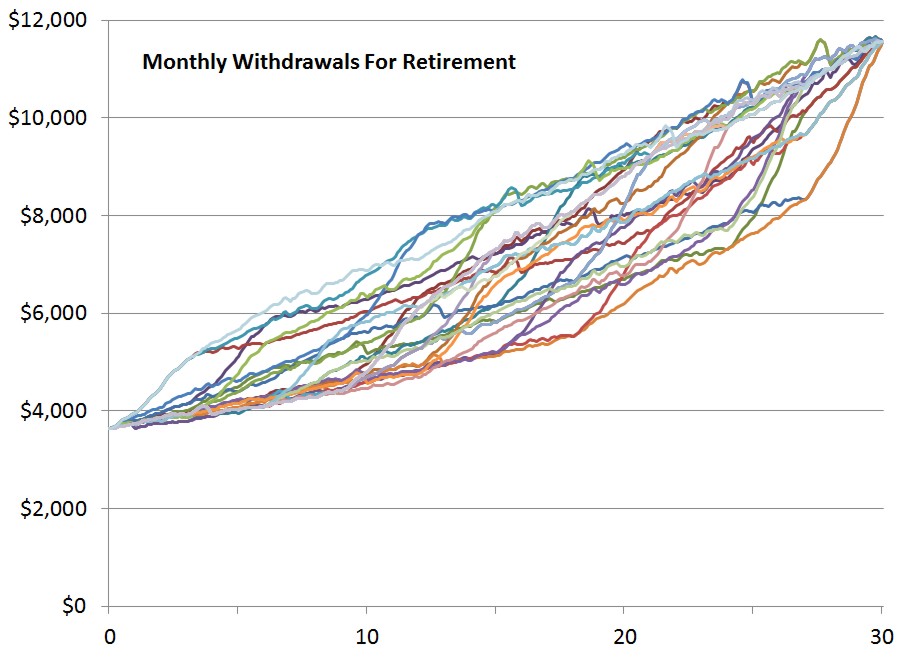

Let’s take our hypothetical 30-year retirement portfolio and put it to the stress test of actually supporting us in retirement. At age 65, the portfolio should be able to support a withdrawal rate of 4.36%.

In our example, that means a $43,600 annual withdrawal taken out monthly adjusted each month by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for the month.

Each scenario begins with a $3,633 per month withdrawal and ends with an $11,567 per month withdrawal. But each scenario takes a different sequence of inflation to reach that final amount.

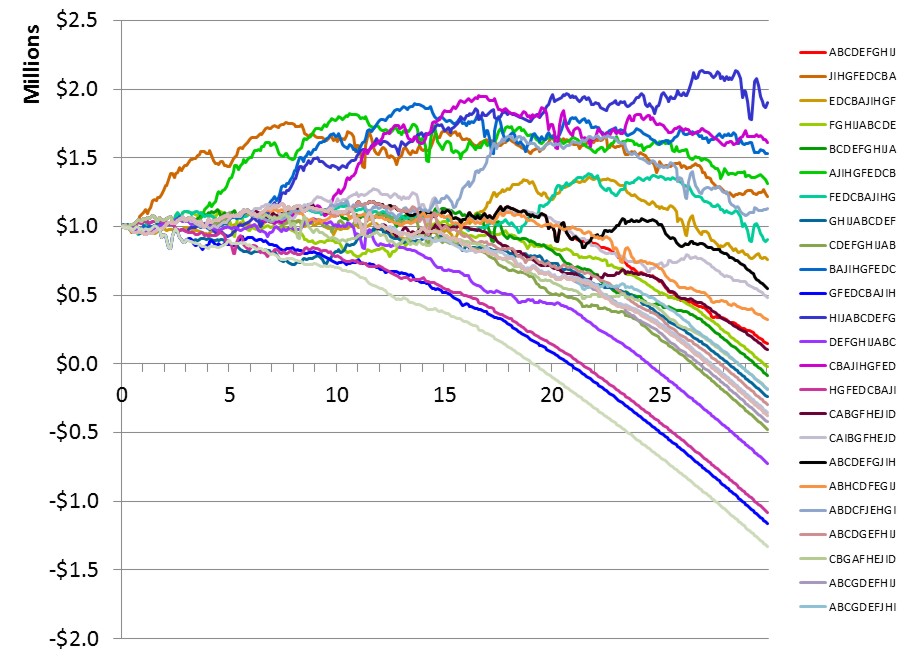

When subjected to such a withdrawal, many of the sequences of the all-bond portfolio end up running out of money. If the portfolio experiences poor bond returns early in the sequence of returns, monthly withdrawals comprise a greater percentage of the portfolio. If the portfolio experiences high inflation compared to the bond return, then the portfolio falls behind on its purchasing power. Having everything in bonds risks not having enough appreciation to overcome poor bond returns early in the sequence.

There is a similar effect for the all-stock portfolio. When the portfolio is burdened with withdrawals, some sequences of returns run out of money during the 30 years. Having everything in stocks risks having to take money out after poor market returns early in the sequence and therefore not having enough money remaining to grow when the markets recover.

But in a 50% stocks and 50% bonds portfolio, none of the scenarios ran out of money. The worst scenario ended with $195,000.

This isn’t an argument for a 50-50% allocation but rather a defense of the craft of asset allocation design. There is an optimum allocation between stocks and bonds for a given withdrawal rate. And the optimum allocation has nothing to do with an investor’s risk preferences.

Finding that allocation requires running tens of thousands of sequences, not just 30. And it should include historical and theoretical scenarios from more than just the past 40 years. Finally, your allocation and your safe withdrawal rate are best adjusted every year during retirement.

It is difficult to value the optimum asset allocation. An all-bond portfolio or all-stock portfolio can be projected and the difference between them measured, as in our example. But the value of not running out of money when making withdrawals cannot be measured. That is why the optimum asset allocation is priceless.

Photo used here under Flickr Creative Commons.