We’ve written before about how the IRS hurts the bereaved by making them calculate a new Inherited RMD divisor each year, including the number of years it has been since they lost their loved one. In addition to being potentially painful (“I was forty when mom died,” you can hear the IRA owner saying, “and it has been 16 years…”), it can waste away the inheritance by taxing mandatory distributions that the heir did not need in the first place.

Luckily for spouses, there is another option.

When a spouse inherits retirement account assets, they have the right to do what is called a “Spousal Rollover” or “Spousal Transfer.” This is simply a transfer of ownership of the assets from the decedent to the spouse either via a rollover to a new account (the cleanest accounting) or by just treating the decedent’s IRA as though it were your own.

If you do the spousal rollover, that means you never need to take inherited RMDs but instead treat the assets as though they were your own, taking RMDs from the account per usual when you are over 70 1/2. This makes a huge difference.

Imagine a woman whose taxable income puts her at the start of the 25% bracket whose spouse dies the year before her required beginning date for RMDs. She inherits a $1M IRA from her spouse and has the options of doing a Spousal Rollover using the Uniform Divisor or using the Inherited Divisor based on the Single Life Table. Regardless of divisor, she will withdraw no more than her RMD for 23 years and reinvest them in her brokerage account. Those investments, whether or not they stay in the IRA or end up in the brokerage account, receive an annualized return of 10%.

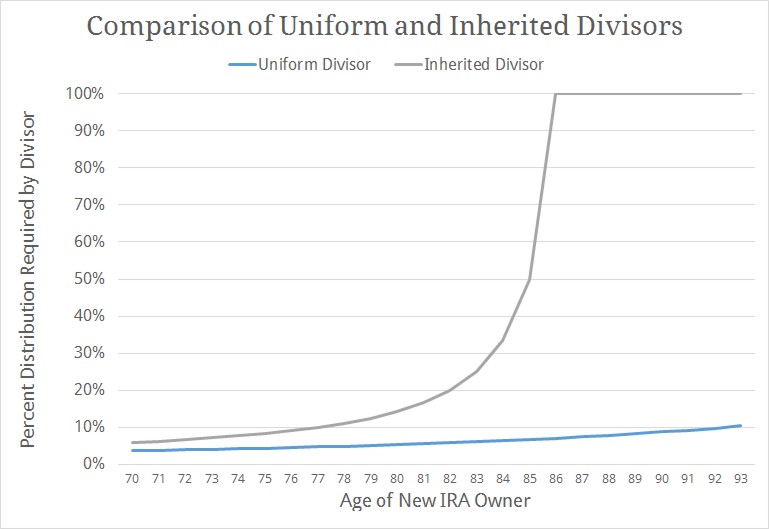

The two divisors work differently. In the first year, the Uniform Divisor would be 27.4 or 3.65% while the Inherited Divisor would be 17 or 5.88%. Then, each year the Inherited Divisor decreases by one, reaching 100% required distribution in 17 years. Meanwhile, the Uniform Divisor decreases more slowly, reaching only 10.42% at age 93 after 23 years of RMDs.

In actual dollars for our hypothetical woman, that looks like this:

If she inherits the IRA and uses the inherited divisor, she will have liquidated the IRA by age 87 and her last RMD would be around $270,000. This easily pushes her from the 25% bracket into the 33% bracket. In fact, over the course of her RMDs, regardless of which divisor she uses, she will see her RMDs move her into higher and higher brackets. Here is a graph of her tax brackets over time for the two divisors:

If she inherits the IRA and uses the inherited divisor, she will have liquidated the IRA by age 87 and her last RMD would be around $270,000. This easily pushes her from the 25% bracket into the 33% bracket. In fact, over the course of her RMDs, regardless of which divisor she uses, she will see her RMDs move her into higher and higher brackets. Here is a graph of her tax brackets over time for the two divisors:

Regardless of divisor, she ends up in the 33% bracket if she does nothing but take her RMD. However, when using the Inherited Divisor, she starts her RMDs in the 28% and quickly rises to the 33%. Meanwhile, the Uniform Divisor sees a steadier and slower increase starting in the 25%.

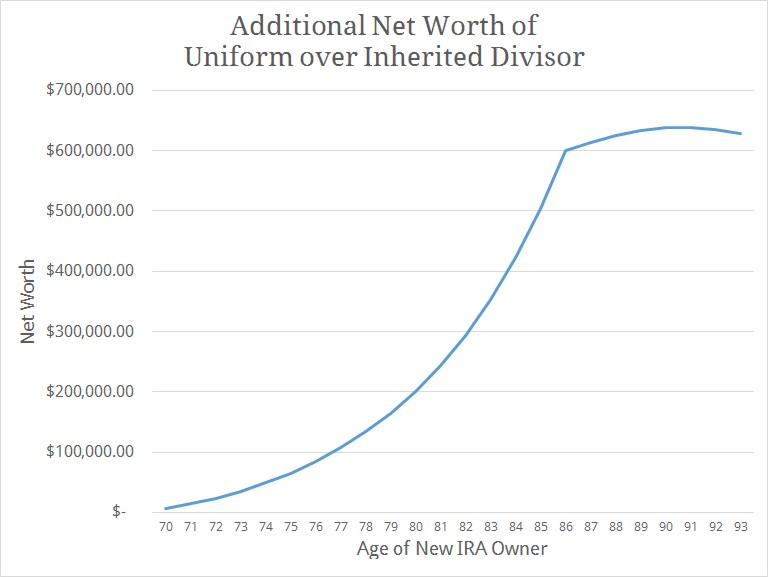

Her net worth over time feels the affects of this tax burden.

You can see that the Uniform divisor has a significant and increasing benefit to her net worth over the Inherited Divisor. As she reaches the 33% bracket with the Uniform Divisor, the advantage that the Uniform Divisor has over the Inherited one in real dollars begins to wane slightly as her IRA balance decreases to only 27% of her net worth. That being said, it is unfair to simply compare the effect of the divisor used on her net worth. More funds left in the IRA are more funds still unburdened by federal taxation, leading to a higher net worth in the short-term, but not the long-term when the money will certainly be distributed and taxed. Instead, we need to compare her after-tax net worth.

You can see that the Uniform divisor has a significant and increasing benefit to her net worth over the Inherited Divisor. As she reaches the 33% bracket with the Uniform Divisor, the advantage that the Uniform Divisor has over the Inherited one in real dollars begins to wane slightly as her IRA balance decreases to only 27% of her net worth. That being said, it is unfair to simply compare the effect of the divisor used on her net worth. More funds left in the IRA are more funds still unburdened by federal taxation, leading to a higher net worth in the short-term, but not the long-term when the money will certainly be distributed and taxed. Instead, we need to compare her after-tax net worth.

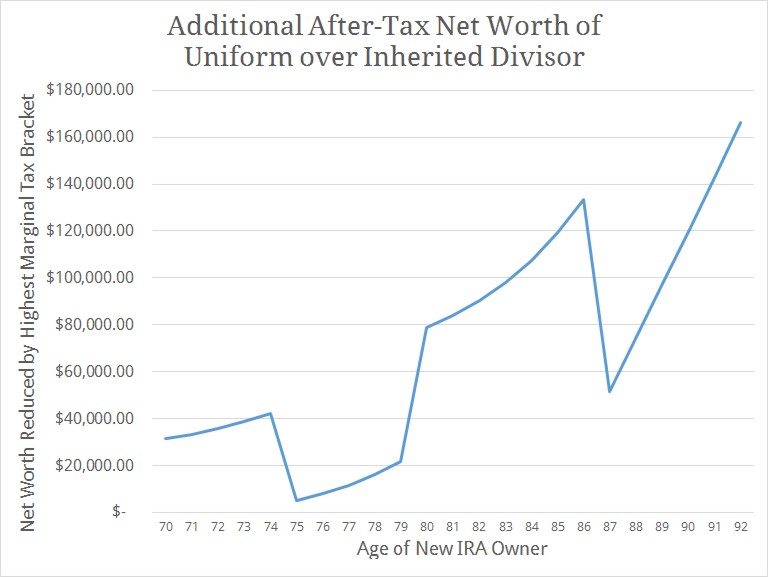

To do this, a decision must be made of what bracket to use, as the two divisors are often in different brackets. I chose to adjust each divisor by the highest marginal bracket in each year. This favors the Inherited Divisor because at age 93 it has no IRA balance to reduce whereas the Uniform Divisor’s IRA balance is reduced by 33%. Here is that graph:

Even when the additional IRA funds retained by using the Uniform Divisor are reduced by 33% to adjust for taxation while the Inherited Divisor has the same funds’ investment gain in the brokerage account reduced by only 15%, the Uniform Divisor still shows significant savings.

Even when the additional IRA funds retained by using the Uniform Divisor are reduced by 33% to adjust for taxation while the Inherited Divisor has the same funds’ investment gain in the brokerage account reduced by only 15%, the Uniform Divisor still shows significant savings.

In addition to protecting more of her assets from the burden of taxation by using the Uniform Divisor, our hypothetical widow also opens herself up to the possibility of Roth Conversions. She is a great Roth conversion candidate because of the bracket movement her RMDs produce for her.

Furthermore, Inherited IRAs cannot be inherited again. The beneficiaries of inherited IRAs must liquidate the assets if the owner of an Inherited IRA passes away. Gaining assets via Spousal Rollover instead allows her heirs to inherit those assets and keep them in a tax-sheltered account (as an Inherited IRA), a great value which varies based on the heirs’ tax bracket.

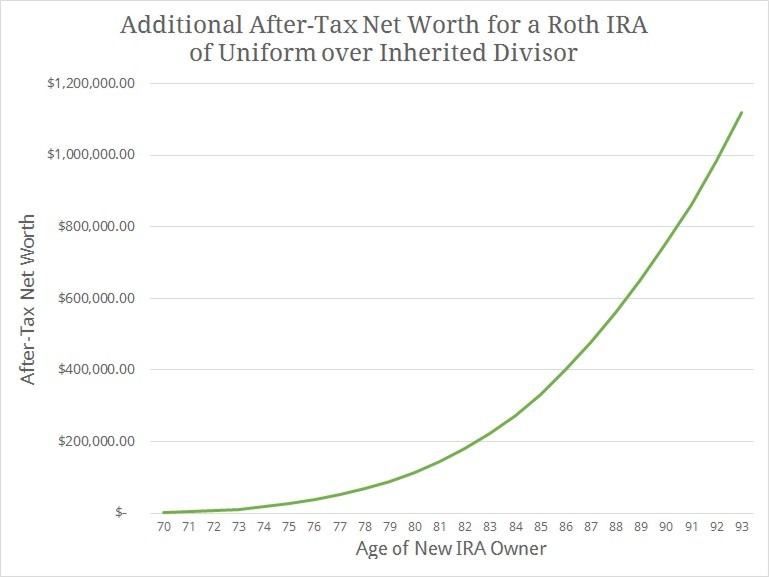

There are even greater potential savings when the IRA in question is a Roth IRA. An Inherited Roth IRA is subject to RMDs, but a Roth IRA acquired through a Spousal Rollover is not.

For this widow, a Spousal Rollover is worth over $1.1 million of after-tax value when the account in question is a Roth IRA, even though the distributions of the Inherited Divisor are tax-free. The burden of capital gains is just that great.

With this much in savings, it would be fair to wonder why the IRS would even provide spouses with the option to use the Inherited RMD rules. The reason is simple: if you are younger than full retirement age (age 59 1/2), then withdrawing any funds from any IRA is faced with a 10% penalty, but there is no early-withdrawal penalty from an Inherited IRA. The inherited divisor provides a costly way for a widow younger than full retirement to access IRA funds without a penalty. However, it is better for her in the long-term to avoid this option and use a Spousal Rollover to take over the assets of her deceased spouse.

Photo used here under Flickr Creative Commons.