In the news, there’s always a financial advisor behaving badly and a lesson to learn from studying the case. The latest example is Anthony Diaz who was convicted on seven counts of wire fraud and four counts of mail fraud for investing in illiquid assets.

In the news, there’s always a financial advisor behaving badly and a lesson to learn from studying the case. The latest example is Anthony Diaz who was convicted on seven counts of wire fraud and four counts of mail fraud for investing in illiquid assets.

We can learn at least five things from Diaz’s case.

1. The eight principles of safeguarding your money protect you.

According to the Department of Justice’s news release :

Diaz persuaded his clients to invest in high risk, illiquid “alternative investment products,” including real estate investment trusts, business development companies, oil and gas drilling companies, and equipment leasing companies.

These are examples of illiquid investments which do not have a readily available market, are hard to price or value, and are difficult to compute what return you’ve received. This alone violates Safeguard #3 that you insist on publicly priced and traded investments.

Elsewhere, CBS News reports that Diaz touted these investments as “‘no-lose’ investments with guaranteed rates of return. ” This is a violation of Safeguard #2: Walk Away from “Too Good to Be True.” You can confidently walk away even if you are unsure why the rosy promises are fraudulent lies.

In several cases, Diaz’s investments also violated Safeguard #1: Do Not Allow Your Advisor to Have Custody of Your Investments as broker-dealers custodied these illiquid assets and reported on them as well.

Lastly, the Department reports, “Documents at trial showed that Diaz regularly earned in excess of $1.5 million in commissions annually. Witnesses described how Diaz spent his money on expensive automobiles, a dozen properties across the United States, and frequent vacations to exotic locales.” This violates Safeguard #8: Avoid an Advisor with a Lavish Lifestyle.

While the rules of our safeguarding series may sound basic, do not underestimate their power to sniff out and protect you from a con.

2. Compliance paperwork does not protect consumers.

FINRA and the SEC suggest that you can look up your financial advisor online via websites like BrokerCheck, a free tool from FINRA that can help you research the professional backgrounds of brokers and brokerage firms. However on websites such as these, you will find people who, although registered, are still ripping you off.

FINRA and the SEC suggest that you can look up your financial advisor online via websites like BrokerCheck, a free tool from FINRA that can help you research the professional backgrounds of brokers and brokerage firms. However on websites such as these, you will find people who, although registered, are still ripping you off.

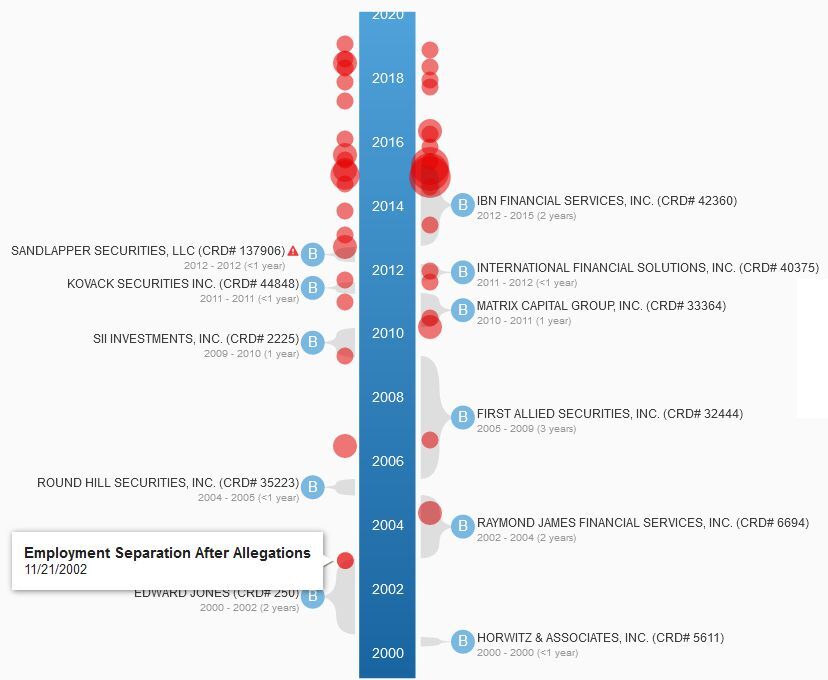

Having a national registry where you report on the tarnished record of bad actors doesn’t seem to weed out bad investment advisors any more than a national registry could clear up poorly behaving police officers. Anthony Diaz’s BrokerCheck record is a prime example. The document is 104 pages long and is tarnished with a history of vague employment terminations.

I’ve taken a screen capture after hovering over his first violation back in 2002 when Edward Jones let him go for (supposedly) providing inaccurate information to a field supervisor. Raymond James then hired him. After a client alleged unauthorized trading and another client alleged forgery, he was again quietly let go. Neither of these clients received any compensation.

The next 16 years of customer complaints and supposed violations are blamed on anything and everything except the advisor. They are filled with excuses such as “the client now believes she did not say to do so,” “His main complaint concerns the Albridge (reporting) system,” and “this agreement … shall never be treated as an admission … of a violation of any law.”

One client’s allegations in 2010 were refiled in 2014. Both complaints were denied.

Regulation annoys the good guys, and doesn’t stop the bad guys. You can’t regulate crooks.

3. Many bad actors don’t realize how bad they are.

When judgements went against Mr. Diaz, he commented, “I vehemently assert my innocence to these allegations. I believe these are the work of one or two individuals that are soliciting these complaints. All I ask is an opportunity to clear my name.”

As the Department reports:

In pronouncing the sentence, Judge Mannion also noted that Diaz had made “no showing of remorse” and queried, “Are you such a con man that you don’t know you’re a con?”

Most if not all fee-and-commission based advisors have convinced themselves that they are putting their clients’ interests first despite the inherent conflicts of interest in the compensation methods of their companies. They sleep at night with an ignorant but clear conscience, many not even knowing how much their clients actually pay or how much damage their bad advice actually does.

4. Commission-based firms can afford to hire whomever.

In the commission-based world of financial services, employees are often only given a small base salary. The bulk of their compensation then comes from commission-based activity. Proponents of this model would argue that incentives matter and that compensation should be based on merit. This method of compensation is often referred to as the “eat-what-you-kill” model of employee compensation because your take home pay is dependent on how much you can convince your customers to spend.

There are several problems with this compensation model, but one of them is that there is little cost to the parent company at hiring whomever. If you hire someone and they are bad at selling the products, then you don’t pay them very much. If you hire them and they are great at racking up commissions, more power to them.

In this way, bad actors often make the rounds of being hired and fired across several dark side firms. In total, Diaz worked for 11 firms over 14 years. Five firms discharged him, and he had 55 disclosures during his working career with more coming in after he was bared by FINRA.

5. A compliance department is no substitute for a culture of compliance.

During much of this time Diaz was supposed to be supervised, but in some cases his supervisor was enabling his career on account of the commissions paid to the supervisor. In other cases, Diaz was dismissed as quietly as possible when wrongdoing was suspected. Supervision at these large firms did not help clients nor avoid fraud.

Consumers often presume that an advisor associated with a large commission-based brokerage firm will have a team of managers supervising their advisor. This is a misconception. At large firms, compliance is often done by a team of lawyers at corporate headquarters, while the individual advisor at a large brokerage firm may have no more compliance, ethics training, or oversight than whatever seminar attendance is required every two years. One of the most common Securities and Exchange Commission violations found at large firms is failure to provide adequate supervision and monitoring of what their commission-based advisors were doing, often in order to generate the largest possible commissions. Incentives matter. With the wrong incentives in place, it can be difficult for even well-intentioned advisors to overcome the subconscious temptation to rationalize their actions.

What is more, large commission-based firms pay small salaries and big commissions. If you don’t push the product, you don’t cost the firm very much. For this reason, they can hire anyone and simply see if they work out. If the new hire doesn’t turn enough product, they’ll either let themselves out from lack of compensation or the firm will cut them loose.

Summary

I’ve been asked if investors should trust their financial advisors. You may be surprised to hear that my short answer is “No.” Given all the greed and deceit in the world of financial services you shouldn’t have to trust your financial advisor. You should make sure that you have taken careful steps to safeguard your money. Make sure that there are no incentives or structures in place to jeopardize the safety of your money. To help you implement this, we drafted eight principles to safeguard your money.

We believe following these principles provides a better safeguard than checking for past violations.

The total judgement against Mr. Diaz was $4.3 million to be paid to 17 former clients . May his crime be a lesson to help others avoid his kind.

Photo by Balaji Malliswamy on Unsplash