The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is responsible for enforcing Rule 206(4)-1(a)(1) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940

that reads, in part,

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is responsible for enforcing Rule 206(4)-1(a)(1) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940

that reads, in part,

“It shall constitute a fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative act, practice, or course of business . . . for any investment adviser . . . , directly or indirectly, to publish, circulate, or distribute any advertisement . . . which refers, directly or indirectly, to any testimonial of any kind concerning the investment adviser or concerning any advice, analysis, report or other service rendered by such investment adviser.”

The SEC notes that testimonials also “include any statement of a client’s experience or endorsement.”

This anti-testimonial rule prohibits advisors from promoting any statement of a client’s experience or endorsement. It also requires them to stop any testimonial from being distributed that they are reasonably capable of preventing.

The anti-testimonial rule has been interpreted to prohibit even a “Like” on Facebook or an endorsement on LinkedIn depending on the content of the post.

Each firm must designate a chief compliance officer (CCO) who is held legally responsible for the firm’s compliance to these and other regulations. The anti-testimonial rule is well known among CCOs because the rule has been interpreted broadly in the past.

Those in the marketing profession are especially surprised by the rule. Their first piece of advice typically is “You should include client testimonials on your website.” They are astonished to learn this most basic marketing technique could cause the CCO to be taken away in handcuffs.

The rule attempts to stop fraudulent marketing. Just because one client raves, “She helped me retire at age 56!” doesn’t mean the advisor can help you retire so young. Thus to use this testimonial in marketing materials and imply the results are repeatable would be deceitful.

The rule prevents more than just client testimonials. The endorsement doesn’t have to be about the advisor’s investment management to be illegal. The content could even be tangentially related to the investment advisor, endorsing his or her work ethic, for example, and still be prohibited.

Even quoting someone saying an advisor “helps people” or “puts the client’s interests first” would violate the anti-testimonial rule. Keep in mind that the truthfulness or worthiness of the testimonial is irrelevant. Quoting the statement would still be considered fraud.

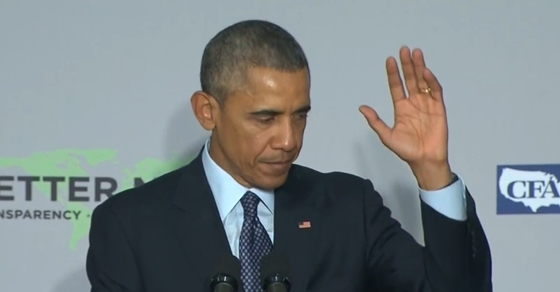

On February 23, 2015, President Obama argued in front of the AARP that the financial industry doesn’t have enough rules and regulations. He singled out financial advisor Sheryl Garrett and offered her a glowing testimonial.

Obama’s praise included saying that Garrett got into the field to help people and was, “trying to do the right thing.” He testified to her good motives and commented that he was proud of her, a ringing endorsement of her worthiness.

He even fabricated a “somebody who is competing with her is selling snake oil.” He complained that, “she’s losing business and ultimately, those clients are going to lose money” because they aren’t choosing to sign up with Garrett, a clear validation of her services.

Sheryl Garrett may very well deserve praise. But if she could have prevented the president from saying this, his public endorsement violates the SEC’s anti-testimonial rules.

To be clear, although Garrett was contacted in advance by Obama’s speechwriters and asked a series of questions as well as invited to attend the speech, she may not have even known the endorsement was coming.

Even if she is innocent of abetting or soliciting an endorsement, to comply with SEC regulations, Garrett is not allowed to refer to the president’s endorsement.

This means removing any social media posts she can and remaining completely silent about the endorsement on her website. It might even mean posting a disclaimer stating, “In accordance with SEC law, I have not asked for nor am I circulating any endorsements or testimonials. Please help me comply with this regulation.”

But instead, the Garrett Planning Network website posted the endorsement, another unmistakable violation of the SEC rule, and used Obama’s comments as part of their advertising. Many more Garrett Planning Network advisors followed suit, circulating the commendation on their own websites.

All of this is an especially glaring violation because Sheryl Garrett is the CCO of her firm. She, of all people, should have known better than to use and encourage the endorsement. Will the SEC give Garrett a citation? Of course not. However, from the blind eye of the law, she has violated the SEC regulation.

Like us, you may think these rules are ridiculous and should be repealed. Other rules are far more important in helping safeguard a client’s money. But that is not the focus at the SEC. They take rules like these very seriously and cite financial planning firms for the smallest of violations.

The SEC has a rules-based enforcement system even though the fiduciary standard is based on principles. No such thing as “fiduciary rules” exists, just as no set of rules will make you a good spouse. A fiduciary is held to a higher standard than just obeying a set of rules.

Much of what Obama parroted in his speech was correct with admirable sentiments. But the administration’s approach is to establish more rules so anyone deemed a bad advisor will be caught violating something.

The Department of Labor and the SEC are both staffed by lawyers, not financial advisors. They don’t concern themselves with the impact of their rules on the very fiduciaries Obama says he wants to protect and encourage. But positive sentiments do not justify greater regulation.

We should always be wary when a noble cause such as trying to get people adequate health care or sound financial advice is used to justify greater governmental power, regulation and control of another sector of the economy.

There are certainly people in the financial industry who, through intention and/or incompetence, are not acting in their clients’ best interest. However, that does not justify giving more power to people in government to do things that are worse. Additional regulations will not help protect the consumer, and the existing rules are already very burdensome.

As economist Milton Friedman wrote, “Concentrated power is not rendered harmless by the good intentions of those who create it .”

We would rather compete with an evil snake oil salesman than have massive compliance and arduous rules stand in the way of our fiduciary principles.