How did mutual funds come to dominate the entire capital markets landscape? Answer: an epochal shift in the 1980s, due mainly to the invention of the 401(k). Only recently have funds begun flexing their muscles in corporate government questions, although they remain largely passive investors.

How did mutual funds come to dominate the entire capital markets landscape? Answer: an epochal shift in the 1980s, due mainly to the invention of the 401(k). Only recently have funds begun flexing their muscles in corporate government questions, although they remain largely passive investors.

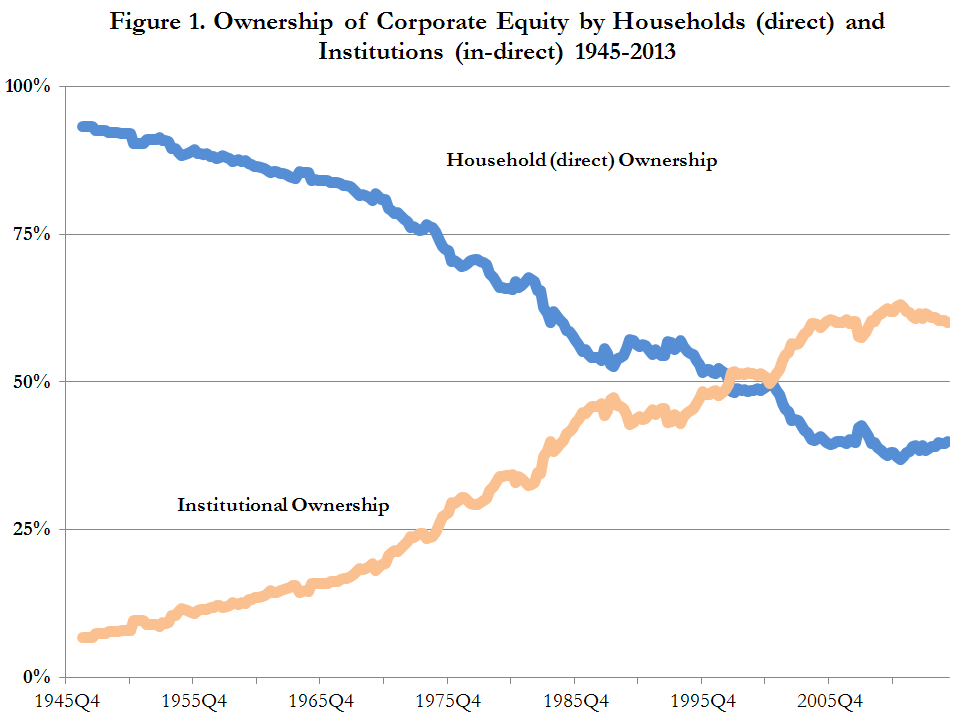

To see how this all happened, here’s a quick history of equity ownership over the last 65 years: Since the end of the World War II, the ownership of publicly traded American corporations has radically shifted hands. As the deck gets reshuffled, all the market players must adjust their strategy.

Domestic stocks have offered significant growth to investors throughout its history. Public policies encouraging economic freedom and entrepreneurial investment propelled an enormous growth in the total capitalization of the U.S. stock market. According to Federal Reserve data, the total capitalization of the US equity markets grew nearly 300 times between 1945 and 2013.

During this period, a major shift occurred that only recently has moderated.

Figure 1 shows that in 1945, 93.2% of all stocks were owned directly. These independently wealthy investors were often the family members of the tycoons who had amassed large fortunes building the business in the first place. In contrast, by 2013 only 40% of all stocks were held directly.

The growth of corporate retirement plans tracked the economic boom after World War II. Postwar peace and prosperity offered expanding benefits to the American worker. Generously funded pension plans became a staple at large corporations, and these plans began increasing their equity exposure as assets grew.

As retirement plan wealth increased, capital markets became more fractionalized. Millions of retirement plan participants were now represented across a myriad of new and existing retirement plans. But decentralization brought along a new set of challenges. Ownership was broken into so many tiny pieces that no one investor had much influence.

As individual investors lost representation, institutional investors who oversaw their portfolios gained influence. These institutional owners are legally considered fiduciary stewards for the individual. They are required to vote on the board of directors and other governance issues.

But critics have long derided these institutions as absentee owners. In the absence of a vocal shareholder base, an excess share of the rewards of capitalism went to corporate executives and institutional intermediaries like mutual fund companies charging high fees. John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard funds, describes this relationship between these two groups as a “happy conspiracy.” Both corporate managers and institutional owners had little reason to hold the other accountable for charging excessive fees.

Although the meta-trend points to the steady rise of institutional influence over the last 60 years, the story becomes more chaotic when you delve into these numbers. Over time, different categories of institutional investors grew in power while others fell. This turmoil creates challenges for the development of corporate governance oversight.

As you can see in Figure 2 (using data also from the Federal Reserve), insurance companies began on top, but their dominance quickly waned as investors found more efficient methods to seek investment growth.

Fund companies (dark blue) and private pension funds (red) appear to have an inverse relationship that is only partially accurate. Fund ownership was growing all along but not nearly as quickly as pension funds for the first 30 years. The ascension of private pension plans from 1950 to 1980 is one of the more important chapters in the complex history of corporate America. The only comment I will make here is that the rise and fall of these pensions corresponds closely to the rise and fall of union influence.

The turning point was 1982, a peak for private pensions and a nadir for the percentage of corporate equity owned by mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). This was only a year after the Internal Revenue Service first approved 401(k) accounts.

Since that time, many parent companies abandoned their pension plans – which paid workers a guaranteed retirement benefit, derived from year of service and final pay – in favor of 401(k) plans that invest primarily in mutual funds.

How are these mutual funds and ETFs handling their newfound position on top of the capital market hierarchy? My previous column, “Mutual Funds Offer Good Governance Assistance,” bestowed the award of “most improved” which isn’t exactly an endorsement. Now that fund companies sit on top of the capital markets hierarchy, investors have every right to know how these behemoths are protecting investor interests. In the sage wisdom of Winston Churchill, “the price of greatness is responsibility.”

Photo by BiblioArchives used here under Flickr Creative Commons.