Steve Goldstein of MarketWatch has a nice article entitled “Here’s the price to be paid for listening to ‘Armageddonist’ predictions from the likes of Soros, Icahn and Gundlach

.”

Steve Goldstein of MarketWatch has a nice article entitled “Here’s the price to be paid for listening to ‘Armageddonist’ predictions from the likes of Soros, Icahn and Gundlach

.”

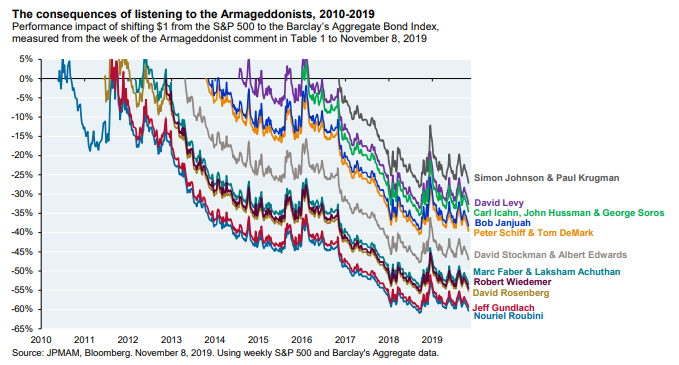

In the article, he quotes the analysis of Michael Cemblaest who computed the consequences of shifting money from the S&P 500 and putting it in the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index in response to “Armaggedonist” predictions. Included in the articles is this graph.

We’ve warned about the cost of listening to dire market predictions and trying to keep some money safe. We have also warned about the importance of learning how to judge media content and the dangers of reacting to the media.

At least some of these doomsayers have their own agenda for pushing a dim view of the markets. David Harsanyi in a National Review article entitled “Paul Krugman: Always Wrong, Never in Doubt ” writes:

Some seemed almost giddy about the political prospects of a downturn. Others just said what they felt. “I feel like the bottom has to fall out at some point,” Bill Maher explained at the time. “And by the way, I’m hoping for it because I think one way you get rid of Trump is to crash the economy. So please, bring on the recession.”

One of the nation’s leading doomsayers has been the New York Times’ perpetually mistaken Paul Krugman, who warned shortly after the 2016 election that Trump’s victory would trigger a global recession “with no end in sight.” We could file that under “post-election hysteria,” but as late as April of this year he was still telling crowds that the bond-market signals predicted “a pretty good chance of a recession sometime in the next year or so.”

The economic and investment success during the Trump presidency has been difficult for liberals to accept, but it shouldn’t be a surprise. Very few things that government does helps the economy, but taxes is one of the exceptions to that rule. When you reduce corporate taxes you increase their earnings. Larger earnings are either (1) given to employees and reducing unemployment, (2) given to customers to increase their purchasing power elsewhere, or (3) given to shareholders justifying a larger share price and pushing the market higher.

Goldstein concludes his article with:

To be sure, of course, a recession will come eventually. But Cembalest’s point is that the recession would have to be incredibly severe for investors to be rewarded by heeding dire advice. “Using rough math, a sustained, multi-year bear market with 35%-45% declines from peak levels would be needed to reverse many of the opportunity losses shown in the chart,” he says.

Between 1929 and 2008, the United States had 14 recessions, which on average is a recession every 5.6 years. Even if you could have anticipated every recession, jumping out of the markets every 5.6 years would have been a disastrous investment strategy.

We do not try to time the markets and instead we believe it is always a good time to have a balanced portfolio.

Photo by Elijah O’Donnell on Unsplash