Our firm is probably one of the only firms with a corporate bible verse from Ecclesiastes 11:2: “Divide your portion to seven, or even to eight, for you do not know what misfortune may occur on the earth.”

The principle of asset allocation is as old as Solomon was wise. I was already familiar with the Talmud’s asset allocation strategy when I heard it referenced again in Jim Grote’s article “The Talmud Strategy” in Financial Planning magazine:

“Let every man divide his money into three parts, and invest a third in land, a third in business and a third let him keep by him in reserve.” So it is written in the Talmud, a record of debates among rabbis about Jewish law dating as early as 1200 B.C. And so it is written on Page 1 of Asset Allocation: Balancing Financial Risk by Roger Gibson, first published in 1989.

Gibson is not Jewish; he found the saying from the Talmud in a book of quotes and liked it. But he has a penchant for history – he lives in a pre-Civil War farmhouse north of Pittsburgh – which has taught him one important lesson: Slow and steady wins the race. …

In his modern update on Talmudic investing philosophy, Gibson defines “land” as real estate investments, mainly REITs (he doesn’t consider a home an investment asset); “business” as U.S. stocks; and “reserve” as U.S. bonds. …

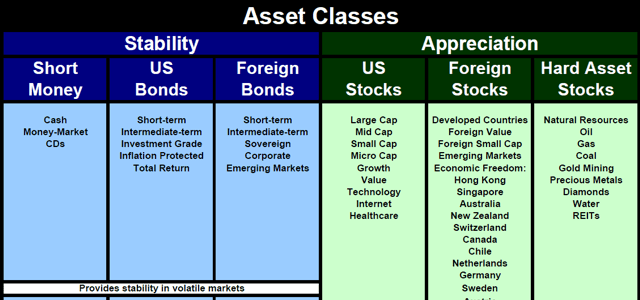

Although its simplicity is attractive, Gibson does complicate the Talmud strategy a bit. He places client money into seven broad asset classes that he divides into two major buckets: interest-generating (short-term debt, U.S. and non-U.S. bonds) and equity investments (U.S. and non-U.S. stocks, real estate investments and commodity-linked securities.

Gibson’s refinement of the basic Talmudic asset allocation ends up very close to our six asset classes: short-term debt, U.S. Bond and Foreign Bonds (for stability) and U.S. Stocks, Foreign Stocks, and Hard Asset Stocks such as real estate and commodity-linked securities (for appreciation). The only difference seems to be that we categorize the subcategories of real estate and commodity-linked securities together under the asset class of Hard Asset Stocks. This is not the norm among the investors whose portfolios I have reviewed. Most seem to be concentrated in U.S. bonds and U.S. large cap stocks. We call that mistake an asset class and a half.

There were two other interesting quotes in the article regarding the psychology of investing. The first quote confirmed that the 5-, 10- and 20-year efficient frontiers reduce the risk considerably because over longer periods of time, returns tend to revert to the mean.

Of course, we all know the equity risk premium makes an enormous difference over time. “If stock market volatility is the disease,” Gibson says, “time is the cure.”

And the second quote reminds advisors and clients alike that financial advisors perform a service when they dissuade people from impulsive decisions that feel right emotionally but statistically are a bad idea.

Gibson describes the relationship between advisor and client as a process that requires the advisor to engage in two strategies. The outer strategy is the science of diversification and asset allocation. The inner strategy is just as crucial, but it is the art of behavioral finance, which can persuade clients to stick to their asset allocations. As Gibson puts it: “Follow your strategy and ignore the evening news.”

Most of the financial news is just noise. Make sure that your asset allocation is both stable and wise.