Imagine that you have two IRAs. In one, you diligently put only nondeductible contributions. In the other, you put only deductible contributions. Both are invested and get a 6% return.

Prior to 2017, you have saved $50,000 of money in your deductible IRA, but now your AGI has crossed the deduction phase-out, and you are switching to funding your nondeductible one. From 2017 to 2025, you contribute $6,500 each year without a deduction, filing Form 8606 each year to track this nondeductible basis.

Each year both accounts’ investments grow.

At the end of 10 years in 2026, you convert the balance of your nondeductible IRA to Roth.

In reality and following basic logic, you should owe no tax on this conversion. You’ve already paid tax on this income and you have been so diligent in your accounting no one should be confused.

But alas, the dreaded “coffee and cream rule” of nondeductible IRAs says that when figuring the nontaxable portion of a distribution or conversion due to a nondeductible basis, you have to prorate each distribution as though it is one mixed IRA with part deductible and part nondeductible.

The analogy is like you can’t take a sip of your coffee without getting part coffee and part cream so too you can’t withdraw from your IRA assets without getting part deductible and part nondeductible.

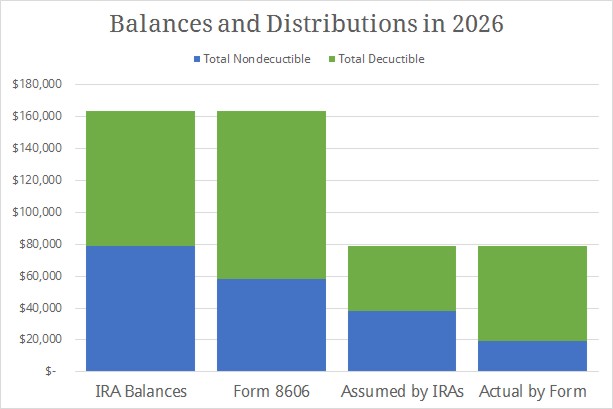

Again, you’d think your accounting would help you. After all, you know precisely what portion is each because you meticulously kept them separate. In 2026, your nondeductible IRA is worth $79,175 and your deductible IRA is worth $84,474. That’s 48.38% nondeductible… but not according to the IRS.

According to the IRS, only the contributions themselves were nondeductible. The growth on those contributions is counted as though they are just regular pre-tax IRA assets. So instead of $79,175 of post-tax assets, the IRS only acknowledges $58,500 (the total of your nondeductible IRA contributions) as being post-tax. That’s $20,675 of what would have been post-tax money had you been able to save it in a Roth IRA that is immediately lost back into the pre-tax deductible side.

Over time, this problem only gets worse as the assets grow and make more of your nondeductible basis shrink as a percentage of the total assets.

To continue the analogy, like how diner coffee gets more bitter as the waitress tops off your cup with more coffee from the pot, so too the growth on your nondeductible assets increases your tax owed by decreasing the percent post-tax assets in your cup.

Sadly, this acts as a hidden tax. In the example, this first Roth conversion would put $10,003 more in your taxable income than if you’d been able to count the full contributions and growth as the nondeductible basis. And this number would just continue to grow (just like your investments do) each year for each withdrawal or conversion.

This is why we say that you only get the full benefit of a backdoor Roth when you have no other traditional IRA assets. How much of the benefit that you lost though depends on a three factors:

How quickly are you going to convert all of your IRAs? The faster you are going to get your entire traditional IRA balance into a Roth IRA, where it will never be taxed again, the better candidate you are for backdoor Roths.

How much are your pre-tax IRAs worth? If you contribute and convert only $6,500 each year but you have $1 million of pre-tax IRA assets, then you’re likely a bad candidate for backdoor Roths.

What is your top marginal rate when you are converting? If you’re top marginal rate is 25% or higher and will be in retirement, then saving $6,500 in your taxable account where it only faces a 15% capital gains tax is cheaper than saving it in your traditional IRA where it will face what is effectively a 25% or higher gains tax.

There are many ways to answer these three questions and, thus, many scenarios where backdoor Roths are and are not a good idea. However, knowing that the investment growth can dilute the benefit can help you determine if you are a good candidate for the scheme.

Photo used here under Unsplash Creative Commons Zero.