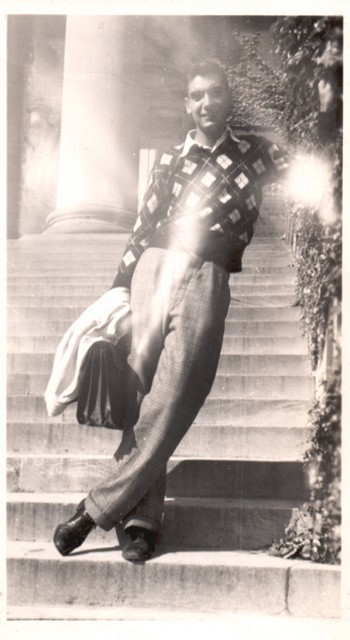

As a part of our firm culture, we celebrate a few unique holidays here at Marotta Wealth Management. One of those holidays is October 6, which we call Founder’s Day. Even though our specific firm was technically founded over the summer of 2000, we celebrate Founder’s Day on the birthday of my grandfather George Marotta, also known as “Papa” to me and “Grand-Papa” to my daughter.

George Marotta brought financial planning to the Marotta family. On his birthday, we celebrate the life, joy, and wealth of that decision. We usually celebrate by gathering as a team all around one big table. Then, we eat lunch and reminisce about our firm history. Like a snowball, we start with memories the most veteran employees have. As we move towards the present, even the newest among us are able to join in with their memories, celebrating what has come to pass.

With many of our team now working remotely, I decided to write this series celebrating my grandfather and his life. This is the second part. You can find the series here.

The Power of $900 of Savings

During the depths of the Depression, James, George’s oldest brother and the eldest son of five, rode his motorcycle from Scotia to Union College (10 miles away in Schenectady, NY) with patches on his trousers to study civil engineering. He worked for Union College cleaning the gym with funds provided by National Youth Administration, part of Roosevelt’s “New Deal.” His younger brother Diamond followed in his footsteps. At Union, they both majored in civil engineering and played varsity football. When James graduated in 1936 during the Great Depression, he had to take a job as a laborer until the economy improved.

Upon their graduation, my grandfather remembers that the Schenectady Gazette had a headline in their paper announcing “Six Italians Graduate from Union.”

All five brothers had successful careers with three of them going into the family business of railroad construction.

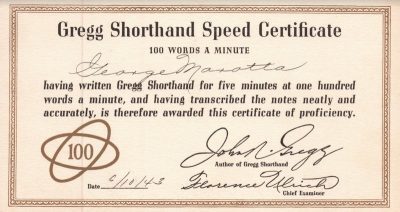

Instead of joining them, my grandfather started college in September 1944 at Syracuse University. At Philip Schuyer High School, he studied commercial courses such as bookkeeping, typing, and shorthand. George took the New York State Regent Examinations and excelled in Bookkeeping I and II, getting perfect 100% scores. His teacher Mr. Kolodny was so proud of George that he wanted him to go to Bentley School of Accounting in Boston where he was sure he could get a scholarship for this student from the tenderloin district of Albany.

George decided to stay closer to home and go to Syracuse University in New York instead. As he headed off to college, George had $900 that he had saved up himself. Right away, the first semester’s tuition took $250.

To help pay the bills, he got a job “hashing” (serving food) at Sims, a female dormitory at the time. He was compensated in both meals and a small stipend.

On the job, he met a fellow freshman named Bettina Lestoque. She was very pretty, nearly 6 feet tall, and from New York City.

“I was thrilled when she invited me to a dance at her female college residence,” my grandfather remembers. “However, I was chagrined to find out that she had used her looks to invite several other males! At the dance that evening, all of her invitees crowded around her to ask her for the first dance. Alas, she did not pick me. However, I was fortunate because there was another tall pretty girl standing nearby. So I immediately turned and asked her to dance. However, she had heard that I was turned down by Bettina and said to me, ‘Second fiddle? Not on your life!'”

They waited out the first dance together and passed introductions. Her name was June Mortlock. She was from Ardsley, near New York City, and was very sophisticated.

George asked June for the second dance and that was the beginning of their friendship,

My papa remembers, “I liked her sooo much that I asked her to go on an exciting date with me to the college bowling allies. There I knew she liked me because she went down to the other end of the alleys and set up the pins for me. Later, I asked her to have dinner with me on Sunday evening because that is when the college dining rooms did not offer dinner. We went to Luigi’s in Syracuse, New York and had spaghetti and some red wine.”

They liked one another and continued dating. They usually went to a movie on Saturday evening and to a restaurant on Sunday evenings. The first movie they saw was “Laura” in 1944.

My grandfather remembers, “I was very busy during the first half of my freshman year because I was running to be president of our class. So I would visit her dorm and give a speech to the girls in her house and ditto for all the other dorms.”

Why You Learn Typing and Shorthand

George returned home for winter break to celebrate Christmas with his family. While there, he got a phone call from his college housemother. She said, “George, there’s a letter here from the government.”

George returned home for winter break to celebrate Christmas with his family. While there, he got a phone call from his college housemother. She said, “George, there’s a letter here from the government.”

“Open it and read the first line,” he replied.

She read, “Greetings.” That’s all she needed to read for them both to know what it was. “Greetings, you have been selected for training and service in the Army;” that’s the way you were drafted. Newly 18 and George was drafted for World War II.

“When do I need to report?” he asked.

”December 27,” was the reply. The current date was December 29, 1944, so that was two days ago. Just drafted and he was already missing from service (AWOL).

He thanked his house mother and called the draft board office in Albany to see what he should do. The officers there said, “Well, Mr. Marotta, how long do you need to get your affairs in order?”

My grandfather thought, “What affairs? I’m a college kid!” but he asked to have until January 2 so he could celebrate New Years with his family. The draft officer said that was fine.

So after a New Year’s celebration, George reported to the Albany draft offices on January 2, 1945.

Being Italian, George remembers that his family was a little embarrassed that Italy had declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941. But his family was loyal to the United States. “I’m sure that was the feeling held by families of German and Japanese descent also. But the Japanese-Americans were not as lucky,” my grandfather muses.

They put him in charge of a couple of other guys who were all new recruits. As the son of a railroad worker, going by train was no big deal for him. From Albany, the recruits took the train to New York City and then a bus to Fort Dix in New Jersey. He was there just a few days before being assigned to Camp Wheeler south of Atlanta, Georgia to get trained.

George remembers that in basic training in Camp Wheeler he was taught how to crawl under barbed wire while, supposedly, real machine gun fire was going off overhead. He never knew if the popping guns were firing real bullets or just training soldiers to function well during the sensory onslaught.

He found he was a sharp shooter and could aim well enough that he got a badge pretty quickly saying so. He and another guy were also selected to be officer candidates. George really liked that idea because officers were allowed to finish their college education before service. He passed all the written exams for the position, but then the officer held a small piece of yarn in his hand and said “Red or green?” George, being color blind, said the wrong thing. It turns out that the other guy, Rhodes, was color blind too. Neither of them could be officers after all.

After basic training, he went home, before being told to report to Fort Meade, Maryland. There, George found out he was going to go to Europe. He called his family with the good news, but then something happened in Washington DC. My grandfather recounts, “They needed more cannon fodder to go to Japan for the invasion of Japan, so they told us, ‘Uh Oh! You are not going to Europe. You are going to Japan.'”

So instead of going to Europe, he was sent to Camp Howze in Texas to receive training in amphibious landings. He was there for a couple of months. In July 1944, they put him on a train to Fort Ord, near Monterey, California. They were there for three days. Even now, when he walks by the area, George remembers crossing the railroad tracks to walk on the very sandy beach as a young man about to ship out. After a short train to San Francisco, he boarded a Liberty Ship with 500 other 18-year-olds. They were headed across the Pacific Ocean for the Philippines and then to invade Japan by the end of the year.

The ship zigzagged across the ocean to avoid Japanese submarines.

My grandfather remembers, “On the way over, we stopped at an island where we had to climb down the side of our ship with ropes into a small boat landing craft that had a front with a ramp that went down. When you hit the land, you went down and could invade the land like the invasion of France. Those little boats. So we went to that island, and they gave us beer. Then, we went back on those little landing crafts and half of the group threw up from the bumpy ride. Then, we had to climb back up the ropes to get back on our ship. And that was all part of our training for the invasion of Japan.”

My grandfather was set to invade Japan’s Southern Kyushu as an Infantryman. He likely would have died on that invasion if it had happened.

However, it took them from mid-July until mid-August to get from San Francisco, CA to Manila, Philippines, and on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb, changing their scheduled invasion plans. So, when they arrived in Manila, George was instead sent by train to a “Repple Depot” (replacement depot) at Clark Air Base on Luzon Island. There, thanks to his typing and shorthand, they classified George as a clerk and assigned him to the Kyushu Base Headquarters in the Southern Island of Japan.

This is the point of the story where my grandfather typically wags his finger and jokes, “So always learn typing and shorthand!!!!” or as he wrote in his article on the topic, “I was lucky to be a 502.”

Drifting At Sea

He was put on a flotilla of twelve small LSMs (landing ships material) that left the Philippines for Japan in late August, a week or so before the surrender was signed.

In a letter dated October 1, 1945 but drafted in August, George wrote to his family from Luzon, Philippines. He reminisced that the Philippines Islands “don’t look glamorous like they do in the movies.” He continues:

Right now I am on the coast of Luzon, part of a small detail, sent here from our main base, to guard some equipment and vehicles that we will eventually bring to Japan with us. The weather here is indescribable. Within the past week, we’ve suffered a typhoon, heavy rainfalls, and blistering sun. The best weather we have here is when it rains, cause then it isn’t too hot, and the rain keeps the dust down on the beach. All my job here is to walk guard down on the beach.

During the trip, they went through a terrible typhoon. During the storm, the landing ramp came loose at the front end of the boat. George remembers, “The flotilla went on ahead as our Navy guys tied down the ramp. I left my bunk below and slept on the seat of a steam shovel right in the center of the ship” so as to not get seasick. He really only left this spot to go “to the door of the mess hall periodically to collect me eats — Saltine crackers,” all he dare dine on.

The flotilla arrived in Wakayama Japan in early September 1945. The soldiers were put up in a factory where “Mitsubishi made those zero fighter planes that were so good” for a few days. Then, George was put on another boat going to Fukuoka, his assignment on Kyushu Island of Japan.

God’s Portable Work

Because George knew typing and shorthand, his assignment was to replace a Staff Sergeant serving a chaplain corp. The guy he was replacing had been in the army a long time and was really ready to go home. So, he only trained George two or three days before leaving. Then, George became the only non-commissioned officer in the Chaplains’ Section of the Kyushu Base Headquarters.

Unlike most in the army, those chaplains were a very learned group. In George’s letter home, he described this as “the language that will be spoken in our offices will be much better than what I am accustomed to hearing in the Army.” They were priests and clergy. The official boss of the group was a Presbyterian minister from Philadelphia. However, the real boss of George quickly became First Lieutenant Frank Carroll who was Catholic.

Shortly after George first arrived, the army Chaplain Carroll, a priest from Boston, pointed to his name tag and said, “Marotta?”

George said, “Yes, sir” and saluted him.

But Frank Carroll corrected him, “Yes, father” because the Pope is higher than even the U.S. President in the Catholic Church.

George said, “Oh, okay. Yes, father.”

Carroll replied, “Mass tomorrow is at six o-clock.”

The next day was a Wednesday, so George replied, “I don’t normally go to mass during the week.”

He replied, “Marotta, you will go to mass and you will serve.”

George said, “Serve? I don’t know how to serve.”

“Marotta, you will learn,” Carroll replied.

My grandfather summarized this story as “That’s the army!” with a chuckle.

My grandfather assisted Father Carroll in his many Masses. They said Mass in Latin at 7 AM every day. Then on Sundays, they said mass every hour in a different U.S. Army location around Fukuoka. George drove the jeep which carried Frank Carroll and the portable altar .

They would arrive at a new camp, and George would set up the altar outside while the priest was talking to the men. Then, when they were all set up, they would say mass. George learned how to say the responses in Latin for the job. Then, they would serve communion. Then, while the chaplain talked to the men, George would pack up the altar and they’d go do another hour of mass.

Before twelve, they would arrive at the harbor of Fukuoka and a small boat would take them to the biggest ship (aircraft carrier or destroyer) in the port. On that ship, all the navy men from all the other ships would have gathered for mass. After mass, the captain would sponsor Father Carroll and George for lunch, and they would have ice cream (a rare treat for the army). “To this day, I love ice cream,” my grandfather notes with a chuckle.

Other times, Father Carroll would be invited to dine with local Japanese families. My grandfather remembers, “Of course, I drove the jeep and had to drive him. And he wasn’t going to leave me in the car while he had dinner. So, I got to go in and have dinner in Japanese homes with the hibachi in the center of the table, cooking the meal right then and there. Wow! That was great stuff.”

War Crime Trials in Tokyo

“By the end of December,” my grandfather reports, “Kyushu Base Headquarters was discontinued. We folded up there, and I was transferred to Tokyo by train.” He was given another job because he knew typing and shorthand. This time, he would serve a supportive role for the International War Crime Trials in Tokyo.

The train journey was harrowing, as they passed right through the flattened city of Hiroshima, which probably was still radioactive by the atomic bomb, on their way to Tokyo. However, there wasn’t long to ponder because his next assignment was starting.

George was assigned to the preparation of the daily court record for the International Criminal Tribunal. The Tribunal of 11 judges was trying General Tojo, who had been the head of the Japanese military dictatorship.

During the trials, they had civilians who were in the courtroom taking testimony in shorthand. Those shorthand pages were then delivered to my grandfather’s unit who would type it up. Then, somebody who was in the courtroom would read that version over and correct it. Then, my grandfather’s team would retype it two more times. One copy was delivered in stencils to be reproduced for the prosecution and defense in English, mimeographed to make a lot of copies. (Somebody else reproduced it in Japanese.) The second original copy would be flown back to DC in the next plane that was going.

“I would work until 8 or 9 o’clock at night producing that daily court record,” George recalls. “That was really something.”

At the end of the trial, General Tojo was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Counter-Intelligence Corp

In Tokyo, George was billeted (housed) in the building of the Japanese Department of Taxation. The accommodations were crowded, a room full of double deck bunks, and the food wasn’t very good. “I served for several months, but I didn’t like my room with 30 other soldiers.”

Because of his commercial skills and experience preparing paperwork though, George recalls, “I was like Radar from M*A*S*H: the officers all depended on me because I knew how to do stuff.” So while he was not housed well, he found out from friends that the commanding officer of the 441st counter-intelligence corp in Tokyo needed an administrative assistant.

“What did I do?” my grandfather recalls with a smile. “I prepared my own transfer papers.”

He had to get the commanding officer of the 441st to request him. Then, his transfer had to be approved by General Willaby (General McCarther’s G2, the head of U.S. Army intelligence in Japan) who was in the Daiichi building. Then, Captain Swartz “who was my boss at the international tribunal” needed to sign off on it.

“When I gave [Swartz] the transfer papers,” George recalls, “I heard expletives that I had never heard before! But when he calmed down, he said, ‘You should have told me, but I need to tell you. These are the neatest transfer papers I have ever seen.'”

And with that, George was transferred out of the crowded Department of Taxation and into a building very near the imperial palace. He went from crowded bunks in the Department of Taxation to sharing a room with only one other soldier in the CIC Headquarters. On top of that, he was permitted use of a Jeep and remembers that on the weekends, he could go all over Japan, especially on the main island, visiting the U.S. Army intelligence posts.

Because the 441st was composed of all intelligence officers, no one wore a rank. However, George was a Sergeant at the war crime trials, and the soldier who previously held this administrative job was a Staff Sergeant, so George got a nice promotion out of the move. Now, he was an Administrative Assistant to the Commanding Officer.

In addition for doing dictation and other secretarial work for his boss, he also did typing work for the intelligence section, “because they had all these reports that needed to be typed up.”

George worked with the counter intelligence team starting around June 1946. He remembers many of the reports were on North Korea. In his 2018 article about it, he writes that “Our main mission at that time was monitoring Russian military maneuvers and training north of the 38th parallel.”

In my interview with him, he explains to me, “Our people in North Korea were watching the Russians train the North Korean military. We already knew Russia was arming them at that time and, I think, China had something to do with it too. Two communist countries turning North Korea into a communist country. There weren’t many in the army who knew shorthand and typing, so I had to take dictation from the commanding officer and from others to prepare these reports. That’s how I knew what was going on in North Korea.”

Almost Done

In December 1946 after having served in the army almost two years, George’s time was coming up when he should be released. However, his boss came to him and said, “George, how would you like to stay on and we will promote you to Warrant Officer?”

George replied, “You know, I have already communicated with Syracuse University and I am going back to school, so that’s my plan. I think I’ll go back to college.”

The next day though, his boss returned and said, “George, if you stay an extra month, I’ll get you — instead of boat — priority to go back to the U.S. by air.”

“Oh! That’s a deal!” my grandfather quickly replied. So he worked another month and then flew back to the United States.

The Air Force in those days was the Army Air Force. So, first they flew him to Hawaii where he waited a few days. Then, they flew him to Camp Beale near Sacramento, CA. where George was given an honorable discharge in January 1947.

Then, they gave him a railroad ticket so he could get back home to Albany, New York.

As you do when you ride American trains even to this day, he first rode to Chicago where he had to change trains. Then from Chicago, he stopped off at Syracuse so he could visit his girlfriend.

“We weren’t engaged yet, but that was June Mortlock,” George comments with a grin. “And I arrived on a Friday and found out she was very popular! She had a date for Friday, Saturday, and Sunday dinner (each night a different boy). She broke the Friday and Saturday dates, so I could have dinner with her. But she kept the Sunday date because I was leaving Sunday morning.”

The dormitories at Syracuse back then didn’t feed you on the weekends, so a cheaper way for a lady to have a weekend meal was to schedule dates with gentlemen. While my grandmother isn’t alive any more, I remember during one family retelling of this story, she chimed in at this point in the story with, “A girl’s gotta eat!”

Then, George finally made it home to Albany. At this point in the retelling my grandfather’s voice takes on a fondness as he remembers how his family teased him when they found out that he had stopped to see his girlfriend before coming home.

Summarizing his time in the military, my grandfather says, “I learned a lot as an eighteen- and nineteen-year-old soldier.”

I’m grateful that my grandfather pushed himself to learn the marketable skills of typing and shorthand and that he taught each of his children (now a doctor, lawyer, and financial planner) the value of an education. I credit much of my own success in life to these family lessons faithfully passed down.

My grandfather turns 96 this year. He is one of my role models and favorite people. What a joy to celebrate him this year!