Last week’s column described how certain critical assumptions can affect retirement planning. Here we discuss how to determine maximum safe withdrawal rates that will not compromise a long retirement.

Last week’s column described how certain critical assumptions can affect retirement planning. Here we discuss how to determine maximum safe withdrawal rates that will not compromise a long retirement.

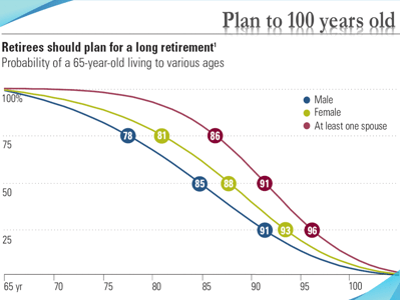

Imagine you knew you were going to die peacefully in your sleep at the end of your 100th year. Becoming a centenarian is more common these days, and it’s a much safer assumption than using average longevity. Half the people live longer than average, and a significant percentage live much longer. So our best case scenario is not just a fantasy.

As you turn 100, you could plan to spend 100% of your portfolio. At the end of the year when you run out of money, you also run out of life, literally dying broke. It makes sense to keep all of your assets in cash or a money market account. Investing in stocks risks a market correction that could leave you short on funds and make your last days miserable.

Now back up a year. You are 99 and could spend about half of your portfolio’s value, reserving the other half for your final year. You will keep money for your 99th year in cash. Money reserved for your 100th year could be put in a CD or a bond for more interest. You should be making a real return on your investments that is greater than inflation.

Imagine you planned on reaching your 99th birthday and several years ago bought bonds to mature at the beginning of each of your last two years. The bond for your 99th year has just matured and is waiting in cash for you to spend. The bond for your 100th year has one more year to mature and is earning about 3% over inflation. So after factoring out inflation, you can spend 50.70% of your portfolio this year, knowing the 49.30% of your portfolio left in the bond will grow by inflation plus 3% to cover a cost-of-living increase for your final year.

Back up yet another year. You can spend a little over a third of your portfolio for your 98th year, just over a fourth for your 97th year and just over a fifth for your 96th year. Gradually as you work backward, the amount of interest over inflation you are earning becomes more significant. Once you establish a laddered bond portfolio of five to seven years, putting those assets with a longer time horizon into the stock market is a good idea.

Investing in fixed income gives you peace of mind, knowing your lifestyle for the next few years will be relatively stable and not depend on the whims of an inherently volatile market. Investing in stocks is appropriate only when your time horizon is at least five years or longer. Therefore, we recommend keeping the next five to seven years of spending in fixed-income investments during retirement. You can keep five years of spending in fixed income if you are aggressive and seven years if you are conservative. Five to seven years is an appropriate range. If you keep whatever you feel like based on an emotional risk tolerance, you may jeopardize your retirement lifestyle.

In our examples we assume you have set aside six years of spending for stable investments in fixed income and allocated the remainder of your portfolio in appreciating equity investments. This money is invested in quality fixed-income investments. There is no reason to invest in “high-yield” junk bonds for the stability side of your portfolio. Junk bonds act like stocks and are liable to fail when you need them most. With your fixed-income investments in quality bonds, you can safely afford to put more of your portfolio in appreciating stocks.

Knowing your retirement spending is relatively secure for the next six years, we suggest putting the remainder of your portfolio into more volatile stock investments to achieve a better long-term rate of return. With this technique, not only do you have a maximum safe withdrawal, you also have a maximum allocation to fixed income: to balance the need for six years of stable spending with the need for appreciation to cover the seventh year and beyond.

For your stable investments, we have assumed a rate of return consistent with fixed income, about 3% above inflation. Assumptions for the equity portion of your allocation are more problematic. In the long run, stocks average about 6.5% over inflation, but in that long a run both your retirement and your life are over. Stocks are inherently volatile. Do not count on any reliable rate of return during your retirement. Past performance is no indication of future results. Just because a 30-year loss in the U.S. markets hasn’t happened yet doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen during your retirement.

You can handle uncertainty in two different ways: throw lots of dice and see what happens or make conservative assumptions. What we learn from the first can help us with the second.

In the financial planning world, throwing lots of dice is called Monte Carlo analysis. It involves running a retirement projection against many randomly generated investment returns to see if that portfolio growth outlasts many random lengths of life. Sometimes returns are selected from history; sometimes they are generated mathematically. Hundreds of assumptions are built into Monte Carlo simulations. As a result, the method illustrates risk better than it actually predicts or protects against it.

We learn from Monte Carlo that every plan has some small chance of failure, and you must accept the possibility that you will need to adjust your lifestyle. We also discover that a string of early bad returns with a high withdrawal rate makes for a difficult recovery. Monte Carlo analysis has so many associated problems, we advise taking the lessons learned and simply making some conservative assumptions.

Assume your stock investments will only average bond-like returns, about 3% over inflation. Normally the markets do much better, but sometimes they do much worse. Working backward from 100, at age 90 with 11 year of spending remaining, you should be able to spend 10.42% of your portfolio.

Continuing to work backward from age 100, we can compute exactly what percentage of your portfolio you can spend if you are retired at any age. Here are those maximum safe withdrawal rates by age, along with the percentage you should allocate to fixed income and still leave enough in appreciating equities to keep up with inflation:

| Age | Withdrawal Rate | Fixed Income |

| 50: | 3.64% | 18.4% |

| 55: | 3.82% | 20.4% |

| 60: | 4.06% | 22.4% |

| 65: | 4.36% | 25.0% |

| 70: | 4.77% | 32.2% |

| 75: | 5.35% | 36.4% |

| 80: | 6.22% | 42.4% |

| 85: | 7.66% | 51.6% |

| 90: | 10.42% | 67.8% |

The safe withdrawal rate never drops lower than 3%. If your portfolio appreciates 3% over inflation and you take 3% out, your portfolio will have grown exactly by the rate of inflation. You can retire the day you are born if you can live off 3% of your trust fund. A 3% withdrawal rate can continue indefinitely as long as your portfolio appreciates annually by at least 3% over inflation.

Every year your portfolio earns greater than 3% over inflation, your standard of living can go up. If your portfolio loses money one year, you may be able to keep your spending constant and wait for above-average portfolio returns to get you back on track.

In this way you can adjust your standard of living dynamically and avoid a “plan once and blindly follow,” on the one hand, and “let my standard of living bounce between feast and famine” on the other. This middle ground keeps lifestyle spending appreciating when the market returns are typical and keeps spending constant in terms of dollars during down markets.

Withdrawal rates lower than these maximum safe rates provide an even safer retirement plan and also allow more of your portfolio to remain invested and appreciate. In addition, withdrawal rates lower than the maximum permit greater flexibility in your asset allocation. With conservative enough withdrawals, you can afford to put more assets either in fluctuating equities or in less appreciating bonds.

Staying under these maximum withdrawal rates in conjunction with a diversified asset allocation gives you an excellent chance of having enough money during your retirement. And if your portfolio experiences average market returns (as opposed to the average bond returns used for planning), you will also leave a nice legacy for your heirs.

One Response

Josh Nelson

So, if a 65-year old retired in the year 2000…what percentage of their portfolio would they have left today? Assuming a 3% annual increase (COLA) I’m showing around 25% of their original investment. A $500K investment with an initial withdrawl of $21,800 would have a balance in 2013 of $117,085. Now you’ve got a 78 year old with less than 120K and spending 30K per year. I used the S&P from January 2000 to January 2013 to arrive at these numbers.

What do you tell this client?